CW: Racism, Islamophobia, strong language

The Oxford Union Librarian, Brayden Lee, has stepped down from his role after making comments described as “racist” by Oxford Union members in an audio recording shared publicly. Lee is heard saying “I don’t know of a time that a British person was running up against a non-British person and won”, and describes the conduct of BAME committee members as “highly tribal”.

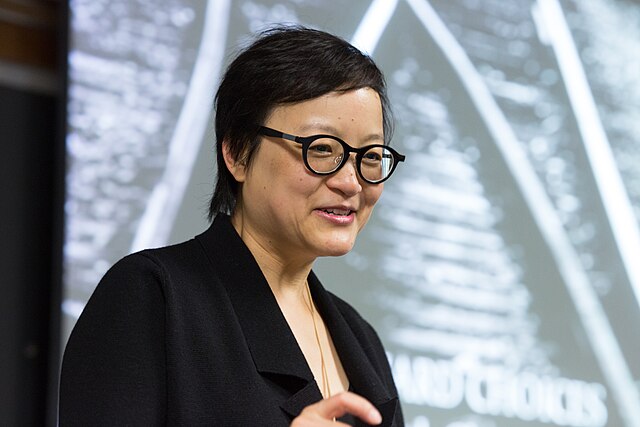

Cherwell has exclusively seen Lee’s resignation, sent shortly before 8pm to the President Katherine Yang and the President-Elect. The Librarian is effectively the vice-president of the Union.

In the recording, Lee remarks that many senior figures at the Oxford Union come from ethnic minority backgrounds. When asked for an explanation for this, Lee says: “The way they see it, for hundreds of years we’ve fucked them over… we’ve tortured them, we’ve killed them, enslaved them, did all these terrible things.

“Why the fuck now they have some level of power [are] they going to give a shred of it to us, after everything we did to them? Of course, they’re gonna look out for their own when the last time white people had power, look what [they] did to them. They need to make sure that white people will never have power.”

Cherwell understands that the recording was made covertly. Lee has stated on social media that someone was “deliberately trying to bait [him] into saying racist things” in order to blackmail him. He said: “I have said some terrible things, and I was totally wrong to do so. I am deeply sorry to everyone, especially those affected by what I said.” Lee was approached for comment by Cherwell.

When discussing Indian and Pakistani members of the Union committee, Lee said: “They’ve got the entire fucking Raj behind them no matter what. Why bother getting rid of one of the few people that isn’t a Taliban [sic] just to put another one? It’s stupid.” The Raj is an outdated colonial term used in the 19th and 20th centuries to refer to British rule in the Indian subcontinent.

Lee also made remarks about former Union President Israr Khan. In the recording, Lee stated that Khan is from Balochistan, “a part of Pakistan that the Taliban operates in”, and alleged that “several of his siblings went on to be in [the] Taliban”.

President-Elect Arwa Elrayess stated on her Instagram earlier today that “Brayden has made the decision to step down from the Presidential race and will resign from his position”. She “unequivocally” condemned racism and said that it requires “accountability and reflection”. Cherwell understands that Lee was going to run for President of the Oxford Union in the elections in week 7 prior to the controversy.

The Oxford Union Rules and Regulations rule 38 (b)(iv) state that officers who resign will be “succeeded by their immediate junior”, which in the case of the Librarian office is the Librarian-Elect, currently Prajwal Pandey. The Librarian-Elect has been approached for comment.

A number of senior Union officials publicly had called for Lee’s resignation. This included the current Librarian-Elect, who described Lee’s comments as “openly racist”. Some of them pointed out the “double standard”, considering the backlash towards former President-Elect George Abaraonye following his remarks about Charlie Kirk’s shooting and the fact that Lee supported the campaign against him during Abaraonye’s vote of no confidence.

The Oxford Union has previously faced allegations of racism, including an incident in Trinity term 2024 when dozens of senior officials had called the society “institutionally racist” after disciplinary proceedings had been “disproportionately targeting individuals from non-traditional backgrounds”, including the removal of, at the time, President-Elect Ebrahim Osman-Mowafy.

The Oxford Union declined to comment.