Everyone’s going a bit crazy these days.

I, for one, am happy to admit that the last few months have been quite bizarre, and I’ve certainly been over-thinking, daydreaming and fantasising more than I usually do. And when we want to over-think, to daydream, to fantasise, the limitations of reality make it quite an unsuitable territory in which to plant our mental playground.

Enter: surrealism.

We normally think of surrealism in terms of art. Dada, Dalí and so on; bizarre juxtapositions and ambiguous non-sequiturs. No story to speak of (it’s hard to become emotionally invested in a melting clock-face), and a breezily playful disdain for fixity of meaning.

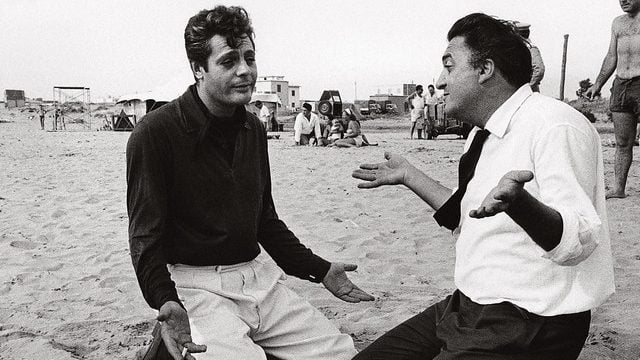

I think much of the best work surrealism ever produced was on film, though. And I think the person who did it best was Federico Fellini.

His films always have a touch of the fantastical about them. As screenwriter, he manged to inject a subtle romance into Roberto Rossellini’s Rome, Open City and Paisan, otherwise pillars of sombre neorealism, and this seed germinated as he directed his own films. La Strada (1954) is a good early example, stuffed as it is with the kind of over-sized eccentrics and magical elegance Dickens would be proud of.

1960’s La Dolce Vita was maybe the hinge – Fellini’s last gasp of real-life air before his plunge into unreality. Even it has a lot of theatricality though: people like Anita Ekberg’s Sylvia, her long dress famously flowing through the Trevi Fountain, just don’t exist in real life.

But then came 8 ½ (1964). In the opening scene, while the audience was still muttering and the lights had only just dimmed, Fellini went full-on Dada. It’s a rush-hour scene, with a thousand lifeless commuters trapped in their cars – our protagonist scrambles to get out of his, and then floats, transcendently, into the Italian cloud, until a rope wraps itself around his leg and yanks him back to earth. “Confused?”, Fellini seems to ask us. “You should be. Now, look at this…”

8 ½, about a director struggling to dream up a film, is very much a film about a director’s dreams. And it’s great, and I love it, but I’m not a director and neither are most people. So, the more relatable film, in my opinion, came next.

1966’s Juliet of the Spirits is maybe Fellini’s masterpiece. It’s about a housewife who is facing an extremely difficult ‘real’ life. She’s stuck in a kind of awkward limbo with little but shallow bourgeois diversions to entertain her, while her husband is quietly, but noticeably, having an affair that she can never quite pin him down on. As her unhappiness grows and patience wears out, she visits various local eccentrics who trigger or deepen intense flights of mental fantasy, which draw on memories and stories about her family.

One of these takes place at a fantastical carnival, with horses and soldiers and a bi-plane that takes off with her grandfather and a dancer. One dream happens in a crumbling religious school, run by the hooded monks of which nightmares are made. The ending, without spoiling too much, scraps the idea that the surreal should be detached from the ‘real world’ at all.

All these sequences flow in and out of the central narrative, riding on the steady stream of Nino Rota’s score, which skips through jazz and music-hall snippets, lilting pipers and blaring circus fanfares. Its playful syntheses distil the energy of the controlled chaos taking place on screen. I think it might be the best film score ever composed. It’s certainly the most fun.

Giulietta Masina’s performance in the central role helps control the film a lot. She has an effortlessly deadpan expression for much of it, contrasting (in a very surrealist way) with the craziness around her.

But I also think she brings agency. Roger Ebert thought Fellini simply used Masina (his real-life wife) as a conduit through which to explore his own fantasies, but I disagree. It’s true she meets neighbours whose sexual flamboyance might have excited Fellini at his lustiest. But they’re only one part of her adventure.

Besides, in the end it’s only Juliet herself that can reconcile the rowdy memories and dreams inside her head. And she does, I think, though it’s left just slightly ambiguous. Any ending more straightforward would be disappointing.

It’s such an entertaining film, and it looks fantastic. The music matches the action so well that I was reminded of Fantasia, and, like that Disney classic, there’s something almost primally satisfying about its synchronisation.

Juliet of the Spirits is also relevant to a world stuck for months with its own thoughts. It’s about those times when our minds run away with us; when we dream about what could happen in the future, or what did happen in the past. It also suggests, tentatively, and with rare glimpses of seriousness, that all these things can be reconciled. Or at least, that it’s a lot of fun to try.

It’s streaming on a service called MUBI at the moment, though I don’t know how long it will stay there for. I had no idea about this until recently, but it turns out that students can subscribe to MUBI for free!

So, if you have a spare two hours and fancy stepping inside a head that isn’t yours for a change, give Juliet of the Spirits a watch. Isn’t that, after all, why watch movies in the first place?

Image via Flickr