Where now those sentences, those syllables,

Loaded like cannon balls on the field of Austerlitz?

Full of the weight and confidence

And destructive power of centuries

Of thought, they were.

If thrown, in seconds they would

Rip through that sheath of wary silence

And the meeting of unsure eyes

Across the battlefield. Much depends

On the ground, the air and the preparedness,

The steadfastness of those opposite,

But also on the surety of the gunman.

Primed himself, by himself, now

Confronted with the chance

To batter down those built illusions

Of peace, the weight of those cannon ball syllables

Returns. The prospect of their release

Had lightened their load on the journey,

But merciless gravity held them now

In the barrel of his throat.

Their choking weight would leave for a moment only,

Returning inevitably with a thudding and crushing

Upon impact. They could not be delivered.

The ground was wrong, the air too quiet.

Peace would rain down weightless,

As those cannon ball syllables retreat

And tear out craters in his heart.

Loaded Words

St Hugh’s JCR Vice-President resigns due to the College’s ‘antisemitism problem’

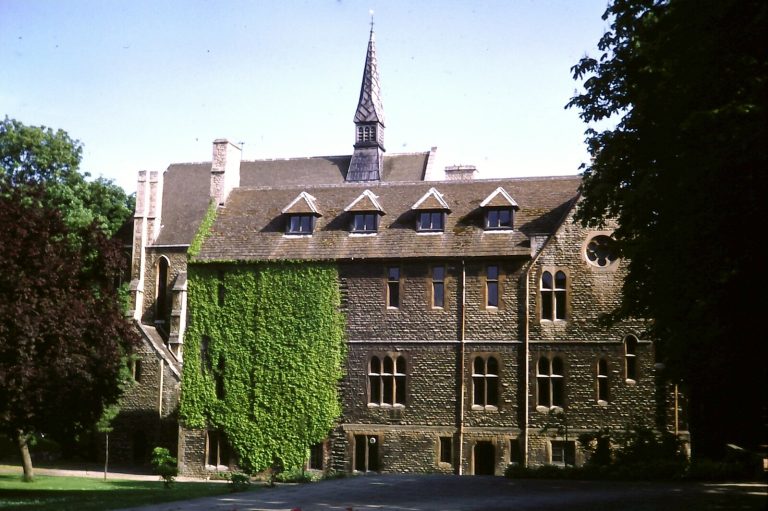

St Hugh’s College Junior Common Room (JCR) Vice-President, Madeline Bryant, announced her resignation via email following a JCR meeting on Sunday 26th May, which she described as an experience of “blatant antisemitism.”

At the meeting, which Bryant reported as three hours long, the JCR debated a motion supporting the demands of the Oxford Action for Palestine (OA4P) encampment.

The motion at St Hugh’s is now up for an online vote among JCR members after it was amended during the meeting to include explicit condemnation of antisemitism in Oxford. Similar motions have been passed in dozens of colleges.

Bryant put forward her own motion during the meeting, which asked for “co-existence, dialogue, and a condemnation of the clear antisemitism that has come from some of the members of the encampment.” That motion was discussed first.

Her motion states that some members of the OA4P encampment “minimised students’ lived experiences of antisemitism or used language that intimidates Jewish students like ‘intifada.’”

It said: “By not actively opposing such harmful rhetoric, the camp has given space to rhetoric that is antisemitic, justifies/refuses to criticise acts of terrorism on civilians, and denies the right of the state of Israel to exist.” It further characterises the slogan “globalise the intifada” as “a call for violence against Jews.”

The motion to support OA4P included a demand that the college cut academic ties with Israel. At the meeting, Bryant argued that St Hugh’s College’s Hebrew language program would effectively end under this demand to which one JCR member allegedly responded “‘So what?” Another member “laughed” when Bryant and another student spoke of their experiences with antisemitism.

Bryant wrote that her resignation “isn’t about Palestinians. It’s about the Jews in Oxford” and concluded her statement by remarking that “St. Hugh’s College has an antisemitism problem.”

The student who proposed the motion to support OA4P, who is Palestinian, told Cherwell that their “voice was minimised” during discussion of the co-existence motion. They also said that the language of the discussion of Bryant’s motion was “appalling to me as a Palestinian Muslim.”

When asked for comment, St Hugh’s College responded that they had “not received any report of alleged anti-Semitism by any St Hugh’s student”, and emphasised that they had “urged any student who experiences or witnesses any unacceptable conduct to report it as a matter of urgency so that the College can investigate.” The College also expressed its commitment to maintaining its Hebrew language courses despite the pressure to cut academic ties with Israel.

Bryant’s resignation follows recent reported instances of antisemitism in Oxford University, including antisemitic graffiti at Regent’s Park College. On 9th May Prime Minister Rishi Sunak met with Vice-Chancellors from UK universities, including Oxford University’s Vice-Chancellor, Irene Tracey, about tackling antisemitism on campuses.

Bryant’s full statement is as follows:

Dear St. Hugh’s JCR,

I am writing to you today to inform you of my resignation, effectively immediately, from the JCR Committee.

I have been serving you since my first term of my first year, first as Environment and Ethics representative and then as Vice President.

As soon as I started at this university, I wanted to work on making it a better place for all students. I can no longer serve this aim.

Last night, I endured a three-hour JCR meeting regarding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. As a Jewish student, I aimed to explain my own experiences of antisemitism which have been directly related to the way in which such debates have been conducted.

I also put forward my own motion asking for co-existence, dialogue, and a condemnation of the clear antisemitism that has come from some of the members of the encampment. I urge you to read this motion, titled ‘Coexistence,’ in full (appended to this letter).

I have watched my peers at this university chant to ‘Globalize the Intifada’ – a call for violence against Jews – but I was not prepared for it to come to St. Hugh’s College.

It is clear to me that some of the students last night did not come in good faith. At one point, when I pointed out that the St. Hugh’s Hebrew language program would effectively end under the Oxford Action for Palestine (OA4P) motion, the response I received was ‘So what?’ with a smile.

It is beyond the pale the blatant antisemitism I experienced in that room – my lived experiences were completely dismissed. Up until this point, I believed that people were just ignorant of reality: the living nightmare that many Jews, myself included, are living. We have faced hate on unpreceded levels in recent months; myself and Emanuel Bor exposed that truth last night, on the record.

Our vulnerability, honesty, and humanity were ignored.

My motion, asking for the basic principle of equal treatment and peace, was sent to a working group – effectively thrown out. The OA4P motion will now be voted on by the whole JCR – a motion that defames and delegitimizes the Jewish people. It denies our ties to our ancestral homeland, dehumanizes Israeli academics and students, and neglects to call out the actions of terrorists.

To every OA4P protestor reading these words, I ask of you: try your best not to dismiss me because I am a Jew who stood up for her people. It is not enough for you to reply by saying there are Jews at the encampment or insisting that Friday night dinners are available.

My Judaism is more than a Friday night dinner. My lived experience is more than a talking point. My humanity cannot be shrugged off.

I recognize that you seek justice for Palestinians, a minority group affected by destruction, displacement, and trauma. Palestinians have suffered immensely, but my resignation isn’t about Palestinians.

It’s about the Jews in Oxford. We sit next to you at lectures. We compete in Torpids with you. We dine in Hall together. We are here and we are human too. We are hurting. And while you will continue to demand justice for Palestine, I asked you to listen to both the Jews in Israel and the Jews in Oxford.

It is clear to me that this JCR either refuses to listen to my experiences, or just doesn’t care. Just as we recognized your suffering, we asked for recognition of our suffering too.

While the Israel-Hamas conflict might be thousands of miles away, the Jews of Oxford are right here. To every bystander reading my words, consider standing up for a small minority who have been bullied for our entire existence.

I won’t give up on trying for dialogue and fighting for my place in this college community. I want you to fight too. Check on your Jewish friends and ask them about their experiences. You might be surprised to hear a silent minority speak up.

And if this letter infuriates you, then check your biases. Why does it bother you when a Jew rightly points out antisemitism? Why is my lived experience worth any less than yours?

I will not serve a JCR that has treated me so cruelly. A JCR that laughed when Emanuel and I spoke. A JCR that refused to engage in productive debate and instead decided to shut down peace and progress.

The meeting last night was an insult to social justice and a win for antisemites everywhere.

Last night, the JCR refused to live up to the values and the community it ought to serve. It is a stain on this college’s history and it should be a stain on your consciences. St. Hugh’s College has an antisemitism problem.

With a heavy heart,

Madeline Bryant

Crankstart tops UK aid, yet falls short of Ivy League

With endowments of over £1 billion, both Oxford and Cambridge stand out among peer British universities for their student support packages. Both universities have made vigorous attempts in recent years to subvert the idea that they are exclusively for those born into wealth. Schemes like Crankstart make Oxford one of the most affordable universities in the country.

Looking across the pond, however, the picture changes. Increasingly, students from top private schools are leaving Britain for the Ivy Leagues. Equally, with generous university support, it may be more realistic for middle-income British students to attend Harvard and Yale over the institution an hour away from home. In light of this, Cherwell investigated: how effective are Oxford’s financial support schemes? And how do they compare to Oxford’s international competitors?

Working and volunteering

As a stipulation for financial support, Crankstart Scholars are “encouraged to complete 25 hours of volunteering work” a year in order to give back either to Oxford or their home community. Oxford bans students from participating in paid work during term time – yet Crankstart Scholars are actively encouraged to participate in term time volunteering.

A meeting of JCR Access representatives hosted found the volunteering “unfair” and one college Inreach Representative commented: “It makes low income students feel as though they need to do free labour in order to earn their place here. It’s quite demoralising for these students who then have 25 hours less than their peers to revise, write essays, do sports, etc.”

No clear support is provided for Crankstart students to complete their volunteering. When asked if they provide additional support related to volunteering, a spokesperson for Balliol told Cherwell: “No – we understood it to be covered by the University.” Similarly, St Anne’s stated that they had no specific general or financial support paths for scholars to aid with finding volunteering.

The introductory handbook states that Crankstart donors “are especially keen that [scholars] encourage school and college leavers to apply to university and promote the benefits of Higher Education.”

The message is reiterated on their website. It includes encouragement for students of lower-income students to complete outreach to lower income background students alongside their degrees. A first-year Crankstart Scholar told Cherwell: “It can feel a bit unfair when scholars have to feel as though they need to ‘earn’ the money they are provided when realistically it is not their responsibility for their lack of privilege.”

While Oxford officially doesn’t allow students to work during the term, some colleges provide opportunities for students to work within college outreach, such as meeting prospective students or running social media. Finding work exclusively during the holidays can be difficult, especially when vacations are often described as “studying away from Oxford.”

Comparison with other universities

Compared to British universities, competitive overseas institutions – especially in America – provide much higher levels of financial support to middle and lower income students. For instance, while a British student with a household income of £32,500 would, factoring in Crankstart, still need to pay £4,150 per year and would not be allowed to work during term, a British student with the same household income at Harvard’s would pay £2,750 per year, and would be able to supplant the entirety of that cost through an on-campus job.

At other similarly-ranked US universities, like Yale, families earning up to £58,972 per year are expected to pay nothing toward tuition, room, or board, and all students are expected to graduate without loans. However, while these American universities provide scholarships and financial aid packages that cover the cost of tuition, room, and board, they lack an equivalent to the British “maintenance loan”, and students are therefore responsible for costs they incur outside food, tuition, and accommodation.

Other top UK universities like UCL and Warwick, give minimal extra funding. Warwick offers low-income students a bursary of up to £2000 a year, and both operate a hardship fund. Oxford and Cambridge have significantly higher endowments than other UK universities, compared to the US where the high levels of wealth are more common.

Student loans

With maintenance loans, English students on Crankstart receive around £14,100 in funding a year, meeting the University estimated yearly living costs of between £12,000 and £17,000. Oxford students on Crankstart are unique in potentially not needing parental financial support with their studies.

The way student loans are provided is not an exact replica of a student’s financial position. Eligibility is decided by one household, ignoring separated parents who both financially contribute and including the income of step-parents or new partners, who may not be financially responsible for the student.

Some students also face parents refusing to contribute to their education. Student Finance England presumes a parental contribution, however there is no legal obligation for parents to support their children after the age of 18, placing some at a significant disadvantage for accessing higher education. In 2018, the Universities definition of estranged was criticised as narrow, leaving only a few eligible for additional support. With a college survey showing that 15 out of 68 don’t receive family financial support University finance does not extend far enough to help all.

Student loans differ between nations within the UK, and even more so internationally. Welsh students all get £12,150, with the amount being loaned or granted shifting based on income. Scottish students studying in Scotland pay no tuition, and all receive a minimum of £8,400. Both Welsh and Scottish students can use their maintenance loans in England.

International students, on the other hand, are often without access to any government financial support. The University “encourages students to explore options for sourcing funding in their home country”, however, these resources are often not available. This limits the diversity of international applicants, restricting Oxford to those who already come from financially able families, especially given that international fees are nearly triple those of home fees.

Living costs

A strength of the scholarship is the control it enables scholars to have over their finances. There is no demand to spend the scholarship on University fees or accommodation costs. This is unlike the nearest equivalent at American institutions, where scholarships must be put toward the teaching fees. The money for Crankstart Scholars has no caveat as to how it should be spent.

A first year Crankstart Scholar told Cherwell: “I think Crankstart has been very beneficial in helping me be able to take part in social activities within Oxford. Though I’m grateful to have financial support, that mainly goes towards essential things (accommodation, bills, food etc) and wouldn’t be able to cover all social aspects of my student life here at Oxford.”

Colleges also offer further support to students on Crankstart, and other bursaries. St Anne’s College told Cherwell: “In the recent past the JCR have offered subsidised tickets to the College Ball for Crankstart and Oxford Bursaries recipients.”

Some colleges provide additional support on top of Crankstart. Lincoln College, who notably provide the most in bursaries, offer additional financial support to Crankstart Scholars.

However for some colleges financial support outside of Crankstart is scarce. When asked about “support, financial or otherwise” that the college provides to students on Crankstart, a spokesperson from Balliol College told Cherwell that there is a JCR grant students can apply for. They further said: “If an application for financial assistance is made we will pay careful consideration to low-income students… [and] make them aware of the financial support available…” but did not offer further detail.

When asked the same question, a spokesperson from St Anne’s College told Cherwell that there is “no specific financial [support].” They also noted that all students can apply for travel grants and hardship grants, which, according to an online report, is for students experiencing “unexpected financial hardship” they “could not have foreseen.”

The Oxford Fashion Gala: A deep dive into design

The Oxford Fashion Gala was an incredible success from start to finish. Designers, models and fashion lovers gathered to share their creativity and passion in a whirlwind of wild looks. While the show itself ran smoothly – a perfect portrayal of the talent Oxford has to offer – Cherwell wanted to delve into the hard work that went into building such a fantastic evening.

In this exclusive interview with one of the wonderful designers and photographer of the evening, Ocho, Cherwell discusses the influences, creative processes and top looks of the Gala!

We began by asking Ocho where her love for fashion stemmed from. While many members of our generation rebelled from the advice of their parents in order to find their aesthetic, Ocho credits her mum for her brilliant style. ‘She keeps a folder filled with cutouts from early 2000s magazines, of both paparazzi and runway’, she said, adding that she herself looked best on occasions where she followed her mum’s advice. Being constantly surrounded by scrapbooks of different fashion trends gave Ocho the nuanced perspective of design that she needed to begin working on her own pieces.

With the 2024 gala’s ode to Issey Miyake catching her eye, Ocho decided to take part in this year’s event. She had attended the 2023 Fashion Gala, and was astounded by the designs, but had never thought she would be taking up this role the following year. She then delved a little deeper into the influences behind her looks, which were based around the ‘Hanbok’. This is a traditional Korean article of clothing, often worn in celebration of ceremonies like New Year’s or other special occasions. Talking about it, Ocho said ‘I think it has such a unique beauty to it – there are a plethora of ways you can style it, and it shifts between minimal to maximal depending on the colour, pattern, and occasion’.

Her vivid blue pieces were a statement of the runway, inspired by the colour of the sea during the day and night. Ocho lives on the coast of California, and so wanted to emulate the ocean in her looks to reflect her environment. She expressed her admiration or her models, Dora and Roya, who brought her vision to life and allowed her to fully captivate the ideas she had for the pieces. Dora’s look was a more traditional representation of the Hanbok; a deep royal blue contrasted by red accents that shimmered on the runway. As the theme was an ode to Issey Miyake, Ocho wanted her designs to resonate with his ‘Pleats Please’ line. In Roya’s look, which was ‘a modernised two-piece Hanbok’ taking inspiration from a bolero top worn by one of Ocho’s friends, pleats were added to emulate Miyake’s style. She loved this addition as the movement of the pleats on the wide leg trousers reminded her of ocean waves.

Of course, Ocho’s designs were a beautiful illustration of her personal influences for fashion throughout her life. However, we could not talk to Ocho without mentioning her spectacular talent for photography. Her pictures captured the essence of every look on the runway, including her own! When asked what her favourite look that she photographed was, Ocho was spoilt for choice. She immediately mentioned the white two-piece that Jacob wore, designed by Clara. The mesh material of the top and the dazzling white patterns on the bottoms made it excellent to photograph. ‘It was slightly transparent, and I loved how it reflected through on the photos with the flash’. Next, she praised OFG’s President, David, and his designs. He made a statement by combining high fashion looks with intriguing materials and balaclavas. In particular, Ocho highlighted his black dress, modelled by Ruby, which was made of a quilted puffer material. She said that it was the most creative piece she saw on the runway! Finally, she mentioned Axel’s pieces, which had also been raised by attendees and president David during the show. She admired their beautiful material, which ‘illuminated really nicely during the runway’.

Ocho drew a connection between the looks she most enjoyed at the gala, and her fascination with the costumes for Dune 2, pointing out that the looks that caught her eye were somewhat reminiscent of the movie’s style.

Ocho’s take on the fashion gala, and her insight into the ‘behind the scenes’ elements of the night, gave us a completely new perspective of how every designer came together to encapsulate the theme. It was truly a beautiful evening, and we can’t wait to see how it all comes together next year!

Summer Eights 2024: Oriel, Christ Church stay on top

Oriel College and Christ Church College defended their positions as Head of the River for the Men’s and Women’s Eights Week races respectively this year. The races, which took place from the Wednesday to the Saturday of fifth week, were tightly contested in the Women’s first division, but all of the top five in the Men’s first division retained their spots from last year.

Eights Week is part of the 200-year old Oxford tradition of ‘bumps’ racing. Boats race single file and attempt to physically bump the boat in front of them, while avoiding being bumped by the boat behind. Crews are ranked within divisions that race each day of the four days of Summer Eights. Bumping moves a crew up in their division, while being bumped moves them down. Crews that are on top of their division then race as the ‘sandwich boat’ at the bottom of the next division; if they manage to bump, they are promoted to the division above them. Crews that are bumped by the sandwich boat are relegated to the division below.

The crew that finishes on top of the first division becomes the ‘Head of the River’. At Eights 2023, Oriel M1 had finished as Head of the River for the Men’s races, as had Christ Church W1 in the Women’s. This year, both teams rowed over (did not bump, nor were bumped) every day to defend their position at the top. While these results suggest stasis from the previous year, there were significant shakeups in the divisions below them.

‘Blades’ are awarded to crews that win Head of the River, or have bumped every day of the four days of the races. Similarly, ‘spoons’ are won by crews that have the dubious honour of being Tail of the River, or were bumped every day. Moreover, since each college often submits multiple crews, there are multiple opportunities for a college to win either blades or spoons, and sometimes even both.

Blades were won sparingly this season; only 14 out of a total of 159 crews won blades. Merton and Green Templeton were the only colleges to have more than one crew win blades, with two each (Merton: W1 and W2; Green Templeton: M1 and M3). Green Templeton M3’s 8-place rise represents the biggest jump this year for any crew. Hertford M2, Balliol W1, and Keble W2 are the only crews to have won blades both this year and last year.

Spoons, on the other hand, were won more plentifully, with 20 crews winning spoons. Oriel’s headship of the Men’s races obscures what has been a disappointing performance from the college overall. Out of the eight crews that they submitted this year across both the Men’s and Women’s races, four (W1, W3, M3, M4) won spoons. This is well clear of other colleges; the runners-up at winning spoons were New (M5 and W3), Catz (M1 and M2), Wolfson (M4 and W2), Antony’s (M1 and W2), and Lincoln (W2 and M2), all with two crews each. The single largest fall for a crew was by Jesus M2 and Trinity W1, both of whom fell six places.

At the college level, the biggest risers were Merton, whose crews across both the Men’s and Women’s races enjoyed a net gain of 15 places. The largest gain in the Men’s races was Green Templeton, whose crews rose 16 places, while in the Women’s, Merton gained 12. The biggest losers this year were, unsurprisingly, Oriel, which overall fell 13 places. In the Men’s races, Catz fell 8 places, while in the Women’s, Hugh’s fell 6.

After inclement weather on the first three days of racing, the final day was graced by some lovely sunshine. Crowds numbering in the thousands visited Boathouse Island to spectate and cheer on their college’s crews. Crews were dutifully doused in champagne and prosecco upon completion of their races, win or lose. And isn’t that the essence of Summer Eights?

An activist’s philosophy: Words matter, but actions matter more

The War in the Gaza Strip has been going on for over seven months. In this time, it has cost the lives of over thirty thousand, injured tens of thousands more, displaced hundreds of thousands, destroyed cities, and brought hundreds of thousands to a state of hunger or famine. However, on the morning of April 9th, I had a conversation that gave me hope.

Alon-Lee Green is a leading Israeli activist. He founded the largest Israeli-Palestinian grassroots movement, Standing Together, in 2015, which aims to ‘mobilise Jewish and Palestinian citizens of Israel in pursuit of peace, equality, and social and climate justice’.

Though Green has received much media attention in recent months, his activism began nearly 20 years ago, while working for a local coffee shop in high school. His attempt to unionise restaurants in Israel led him to be fired from his job; but the story didn’t end there. “A judge ruled they must reinstate me, and after a six-week-long strike we won and gained a collective agreement”, he tells me. The ruling was “historic in Israeli terms, [in demanding] we receive all legal rights for workers”.

Though he “didn’t have the language for it yet”, Green began to appreciate the power of collective action. Nazir, a Palestinian citizen of Israel was one of the five union leaders who stood alongside Green at the time. “For the first time in my life, I understood the power of organising people, even if they are very different from you”, he says. To a young Alon-Lee Green, it had seemed mystical that a Palestinian could lead hundreds of Muslims and Jews in Israel, but from this experience, he saw it was possible.

Several years later, at 22 years old, Green was among the leaders of Israel’s 2011 “social justice protests”, one of the country’s largest-ever protest movements. “It was a crazy and magical summer”, he recalls. “Tent cities and hope spread across the country carried by the belief that we will bring true change”. Yet, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu rejected the movement’s demands and “hope quickly turned to despair”. Despite the setback, Green understood that “leading people is not enough, organising them for the long term is needed” and began to look for a way to enable a unified political struggle, in which Jewish and Palestinian Israelis could be united in their demands.

These earlier lessons laid the foundation of Green’s current organisation Standing Together, a “grassroots movement mobilising Jewish and Palestinian citizens of Israel in pursuit of peace, equality, and social and climate justice”. For Green, its purpose is “to build power in the struggles for peace and against The Occupation, for social justice and for full equality for all the people living here”.

Green tells me that the supporters of Standing Together are unified by a shared understanding, “a shared language, and consciousness about the reality in Israel. What is special about Standing Together’s members and participants is [that] they believe people of all national identities deserve full equality, liberty, and independence”. Standing Together aim, “is not about standing in solidarity with Palestinians, it is a shared struggle for the interests of both Palestinians and Israelis, which will arise from a solution that works for all”.

Although Standing Together is a relatively small organisation, it still receives substantial attention and is criticised across the political spectrum. The Israeli right sees them as the extreme left that is detached from the Israeli public. The Israeli far left criticises it for compromising on the Palestinian cause to increase their public reach. And, the international Boycott, Divestment, and Sanction (BDS) movement opposes it for being “an Israeli normalisation outfit that seeks to distract from and whitewash Israel’s ongoing genocide in Gaza”.

Green seems unfazed by critique, regardless of its ideological origin, believing that Standing Together’s achievements are proof they are doing the right thing. He views such criticism only as an ideological barrier to preventing a larger base of people from engaging with the movement. This philosophy, of prioritising action over speech and efficiency over form, has guided Standing Together over the years and continues to do so during the War in the Gaza Strip.

Throughout the current war, Standing Together has consistently challenged the Israeli public and government, ever pushing it leftwards. They were the first Israeli organisation to demand a cease-fire and the first Israeli organisation that created humanitarian aid shipments to the people of Gaza. Their aid convoys, however, were stopped several kilometres before reaching Gaza by Israeli police forces. When it became clear the shipment would not reach Gazans, Standing Together diverted it to Palestinians in the West Bank.

Beyond Palestine, Israel, and the current war, I asked Green about activism globally. Over the years, Green has learned from movements in the Middle East, Europe, and the United States. For instance, during the global waves of protests in 2011, the Israeli protesters borrowed a phrase from Cairo’s Tahrir Square: “The people demand social justice”. In addition to echoing across national borders, this phrase broke barriers within Israeli society, as Israelis and Palestinians alike supported the cause. “It was chanted in Arabic in Nazareth and Haifa, and in Hebrew in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. It was the first time in Israeli history that the phrase ‘the people’ was not [referring to just] the Jewish people.” The movement had encompassed the entire population, regardless of religious, national, or ethnic distinctions.

In the spirit of learning from international activists and movements, I hoped to get some tips from Green about what individuals who care about political issues should do. Above all else, Green believes that people should utilise their electoral power. “Take your political system very seriously,” he advises. “Your government has a huge impact on your own life and on what happens in Israel, Palestine and around the world. You can create broad coalitions that demand change from your governments”.

Despite the clear dialogue with activists Standing Together maintains across continents, there appear to sometimes be substantial differences in their respective attitudes, specifically towards language. “Occasionally, people think the terms you use are more important than what you really do”, Green says. During meetings with activists in the United States, after Green detailed the actions the movement was taking to deliver humanitarian aid to Gazans, he was asked in response why Standing Together didn’t use what Green terms “buzzwords”. “OK”, he says, “words matter, but actions matter more”. Conversely, Green’s position on language may be one of the reasons why movements like BDS criticise Standing Together and see it as “a normalisation outfit”.

I ended the interview by asking Green about which sources of information he would recommend on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the War in the Gaza Strip. “It’s a good question, but I am not sure I’m the best person to ask this”, he says. Green, as an Israeli, reads mostly Israeli outlets Haaretz and Local Conversation, which offer a “very Israeli angle”, which is informative, but not necessarily what everyone needs. He suggests following local people on social media, who report and film their personal experiences.

In addition to Green’s recommendations, other sources of information can be found through Solutions Not Sides’s weekly news brief, where they provide articles from Arabic, Hebrew and English mainstream, verified media outlets. With this, they capture “what is being said about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict from different perspectives”, without influence from blogs, think tanks or unverified news outlets. Furthermore, Avi Shlaim, Emeritus Professor of International Relations at Oxford and one of Israel’s “New Historians”, recommends two books to understand the conflict. First, Deluge: Gaza and Israel from Crisis to Cataclysm by Jamie Stern-Weiner, published in April 2024, covers the context leading up to October 7th and possible ways forward. Second, he recommends The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917–2017 by Rashid Khalidi, as “a work of outstanding historical scholarship” which “presents compelling evidence for a revaluation of the conventional Western view of the subject”.

Green’s words continue to resonate weeks after our interview, as the war continues and around the world activists escalate their struggles. Green believes everyone has what it takes to be an activist. “We live in a crisis-riddled world where there are many opportunities, but the powerful minority reaps them while the majority suffer.” He says. “Throughout history, what broke these dynamics [of exploitation] was the people who forced change on their political system. We need to remember the saying, ‘if we won’t liberate ourselves, we won’t be liberated at all’ – and that is a real possibility”. Green speaks from years of experience, of both success and failures. But looking at the current state of Israel politically, economically, militarily, and morally, one cannot think his words are overly idealistic.

An ode to the spring onion

Content warning: discussion of eating disorders

I really do add spring onions to everything, you know. They go with my eggs, on my toast, in my tuna and on top of my bolognese. They’re the base of pretty much every pasta recipe I make and I’ve put them in more than a few soups. Every day, I move one step closer to mixing scallion juice into my brownies. After that, who knows. Sorbet, perhaps?

A spring onion slots beautifully into any recipe. It’s got the distinctiveness of chilli or ginger, but cooler and brighter – the perfect way to liven up a basic meal, or add another layer of complexity to something more flavourful. I always keep a bunch or two on hand; they’re practically a necessity for me.

Predictably, of course, I wasn’t always so liberal with my spring onion usage. Up until about five years ago, I’d barely heard of the things, let alone tasted them. For essentially all of my life, I’ve suffered from what people around me at the time called picky eating and now, with hindsight, can fairly confidently be identified as some sort of eating disorder. My preference for basic foods and my tendency to skip meals was only exacerbated by becoming responsible for cooking for myself. During the first COVID-19 lockdown, I essentially alternated between two meals – eggs on toast and tuna pasta. If I didn’t have the ingredients for either, I usually didn’t eat anything.

Things started to change when, standing smack dab in the middle of the Tesco Extra aisle, I had an epiphany: I missed eating vegetables. Alright, it probably wasn’t that dramatic. I don’t even remember why I chose spring onions specifically. But for whatever reason, I came home that day with a bunch of them in my bag. I chopped them up, sprinkled them over my eggs, and that’s when the love affair started. They crept into everything I cooked, meal by meal.

It didn’t end there. Eggs on toast (with spring onion) started to bore me, so I bought an avocado on a whim one day, and, who’d have guessed – it turned out I quite liked avocado. Plain noodles (with spring onion) weren’t cutting it any more, so in went chilli flakes and soy sauce and other basic ingredients I’d always been too scared to try. My spring onions were my safety net. I knew I liked them, and I knew the sharpness of them could sideline any flavours I ended up not liking. What I found, however, was that I did like all of these new ingredients. I enjoyed the taste of the avocado and the textural contrast it added, too. I struggled a little with the heat of the chilli at first but soon enough I was adding it to tomato soup, using its aftertaste to extend the flavour.

My new fervour for cooking only grew. Now that the floodgates had opened, I was looking for ways to make everything I ate more interesting. I learnt the five flavour types, and now I always keep lemon juice on hand for a splash of acid – honey, too, for a sweet undertone. Bored of tinned soup, I made my own;it really does taste so much better. Then, of course, I had to bake some bread to go with it. “You know what goes well with tomato soup? Cheese,” said everyone on the internet, and I’d never liked most cheeses, but I sucked it up, bought the mildest I could find, and sprinkled spring onion all over it. And I enjoyed it! I stopped skipping lunches, because I learnt to love making them. They were a part of my day I actually looked forward to. Finding new ways to combine flavour and texture is something I absolutely live for. Going out to eat has become a lot easier, too; I no longer end up holding back tears in a restaurant because there’s nothing on the menu I can bear the thought of.

I’m not going to call myself a ‘good cook’. My shopping basket gets a little more varied every week, but there’s still whole categories of ingredients I haven’t tried. There’s ingredients I’ll probably never be able to bring myself to try – blue cheese, for one (although I always said I couldn’t stand the idea of smoked salmon, and you’ll never guess what’s sitting in my fridge right now). I regularly burn toast and split sauces. But I still feel a little burst of pride whenever I remember my flatmate saying “oh, wow, you can actually cook!” when he saw me roasting a courgette, because the me five years ago would never have even thought of doing that, let alone adding paprika to the soup it went into.

The soup didn’t actually taste much like courgette, for the record. I put too much spring onion in, and it overwhelmed everything else. I’m not complaining, though – you can never have too much spring onion in your life.

St Antony’s College signs deal with top Chinese university

St Antony’s College has recently signed a 5-year deal with Tsinghua University and received $130,000 to take on two fellows from the University per year. Tsinghua is the top university in China where most leaders of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), including the president Xi Jingping, studied – they have been nicknamed the “Tsinghua clique”.

Some of the $130,000 sum will be paid back to the fellows as a research allowance while the rest will go towards “a number of budget lines” including a management charge for administering the programme.

Tsinghua University does not pay the fellows directly but sends them the money through St Antony’s College. As a result, Tsinghua fellows will be paid by Oxford University and will be employees of St Antony’s College.

Tim Niblock’s, emeritus professor at the University of Exeter, told The Times: “it makes quite a lot of difference in the Chinese system whether they are simply being paid by Tsinghua to do research abroad, or whether they have some kind of a recognised status as part of another organisation. In short, the latter gives them much more kudos than the former.”

St Antony’s, which is known for its international student body, told Cherwell that they have similar partnerships with other universities, some of which are funded by similar means.

Fellowships are either self-funded, funded by specific donations held as endowment funds, or as in this case funded by external institutions.

St Antony’s said the agreement’s benefit to the College is “largely academic. Our fellows and students, based at our various internationally-known area studies centres, have productive interaction with researchers from IIAS Tsinghua, who work on various parts of the Global South on topics of interest to our academic community.”

Asked about criticism they might receive, St Antony’s told Cherwell there are “some [express] reservations… because of objections to Chinese human rights and political issues such as the mistreatment of Uighurs in Xinjiang, the repression of political rights in Hong Kong, and threats against Taiwan, while others believe it is legitimate to engage with academics at leading universities as they are not involved in state policy-making on such issues.”

The announcement of the programme follows a MI5 warning to UK universities regarding national security risks associated with international partnerships. Specifically of concern is sensitive research leaking to competitors in countries like China.

The Tory MP Iain Duncan Smith said about the agreement: “This decision is astonishing… How can Oxford care so little about the freedoms of people?”

Somerville College JCR passes motion calling for Vice-Chancellor’s resignation

Somerville College Junior Common Room (JCR) passed a motion on Sunday evening to release a statement, which included a demand for the resignation of Vice-Chancellor, Professor Irene Tracey, over her response to recent pro-Palestine protests in Oxford.

The motion, which passed with 32 in favour and 5 against (numbers amended 21:00 27th May), was voted on during an emergency meeting which was initially proposed at 22:18 on Friday evening in an email to the JCR, suggesting a meeting time of Sunday 5pm. The date and time was not confirmed until the day of the meeting at 12:17. The full statement was sent out to the JCR at 13:18, after the wrong statement was attached to the initial email. The JCR was not scheduled to meet before next weekend. The turnout represented a small portion of the JCR, whose membership is several hundred.

The statement called for Tracey’s resignation for her “refusal to engage with [Oxford Action for Palestine]” and “her office’s decision to call the police on peaceful protesters” after protesters staged a sit-in at University offices on Thursday. The demand also called the University’s statement, issued after Thursday’s events, “woefully inadequate.”

The call for Tracey’s resignation was one of four demands on the University included in the statement. They also demanded the University immediately engage in negotiations with Oxford Action for Palestine (OA4P); issue a formal apology for calling the police on students; and award “[a]mnesty for all peaceful protesters.”

Police arrived at the University Administration offices in Wellington Square on Thursday morning after protesters entered and occupied the building. 17 protesters were arrested on suspicion of aggravated trespass and affray. One one of the 17 was also arrested on suspicion of common assault. All of the 17 protesters arrested Thursday were subsequently released on conditional bail.

The University’s statement, which was sent to all students on Thursday evening and signed by the Vice-Chancellor and other University staff, described the “direct action tactics” used by the protesters as “violent and criminal”. It further instructed: “this is not how to do it.”

The statement also called on Somerville College to condemn the University for calling the police on protesters, to demand the Vice-Chancellor’s resignation, and to support OA4P and “leverage their position” to pressure the University administration to comply with the group’s demands.

Police entered Somerville College on Thursday afternoon to launch a drone from the premises, after requesting permission to enter the College as part of an effort to maintain the safety of individuals in the nearby protests. Somerville College told Cherwell that the police had “no business” being on College grounds and confirmed that they were subsequently asked to leave by College Principal Jan Royall, after the decision became more “widely-known.”

The College said in a statement on Thursday: “We take this opportunity to reiterate that we support and respect the right of all our students to protest peacefully. We have extended an open invitation to our students to discuss this incident and the wider protests with us should they wish.”

Danae Ali (a second-year PPE student at Somerville), who proposed the motion, told Cherwell the University’s position regarding the protest “puts their students in danger” and said their conduct on Thursday “clearly evidences this.”

When questioned about the low turnout, they said: “JCR open meetings generally have a low voter turnout” and noted that the turnout to today’s emergency session was “about the same” as for regular meetings.

Earlier this month, Somerville JCR passed motions to publish statements in support of Palestine and OA4P’s “liberated zone”. Today’s motion follows several from Oxford college JCRs supporting the pro-Palestine encampment.

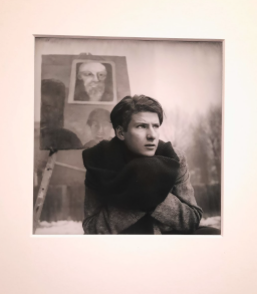

The artist and the photographer: An analysis of Francis Goodman’s Film negatives

The walls of the National Portrait Gallery in London are dotted with an eclectic mix of paintings and photographs. There is no hierarchy based on which the art is displayed, but rather visitors are hit by a wave of portraits as soon as they enter a room in the gallery. The visitor is met by a room of unfamiliar faces and throughout their journey they become increasingly curious about the stories of the individuals who now adorn the gallery walls. One such individual is the artist Lucian Freud, whose rather unconventional charisma was captured by the photographer Francis Goodman in 1945.

Goodman was invited to take photographs at Freud’s flat, 2 Maresfield Gardens, following their initial, and rather spontaneous, interaction at the Coffee An’ in Soho, London. Freud, a young artist who had recently graduated from Goldsmiths’ College, likely perceived such an interaction with a professional photographer as a sign that his art career had just begun. Goodman’s photographs, after the Second World War, which featured regularly in the British magazine The Tatler And Bystander, focused on covering high society, lifestyle, and politics.[1] Yet, the portrait of Lucian Freud was not as organised or calculated: the photographs were taken outside during winter, where the reflection of the cold winter snow on young Freud’s complexion acted as a natural form of studio lighting.

An unusual dynamic is consequently captured between the photographer and artist in the photograph of Lucian Freud. Rather than Goodman directing the sitting, it appears that Freud cultivated his own image as an artist through the medium of Goodman’s photography. As such, rather than the final photograph reflecting primarily on Goodman’s perceptions and insights as a photographer, the hardship experienced by Freud as a Jewish artist in post-war London is revealed. This is especially depicted by the piercing, though distant, gaze of Freud and his folded arms, attempting to protect his body from the cold winter in London. Freud emigrated to England in the 1930s, aged ten, alongside his family to escape Nazism. Whilst Freud was granted British Citizenship, the photograph illustrates the realities of migration as Freud appears unsettled by the harsh conditions of the outside from which the photograph was taken. Nevertheless, whilst a sense of starkness and coldness is portrayed through the slightly blurred surrounding landscape, this is in contrast to the extremely clear and determined glare of Freud himself. The photograph, therefore, was important to Freud as a reminder of the origins of his life as an artist and his ability to navigate the alienating environment of urban London.

The photograph not only depicts Freud as an artist, but one of his own paintings is also visible in the background. Goodman and Freud cleverly synthesise the mediums of paint and photography. The portrait depicts an old, slightly deformed man, who’s glance mirrors the direction of the artist himself. The man in the portrait and the artist are therefore connected, perhaps through similar shared experiences of isolation and hardship. Freud is sitting and his lower position on the ground means that the portrait is depicted above the artist. It is almost as if Freud was now directed by the art he created and the photograph reveals how interrelated his emotions or personality were to his artistic process.

Goodman’s other film negatives also reflect the unconventional beginnings of Freud as an artist. For example, one photograph depicts Freud with dishevelled hair placing the spout of a watering can into his ear. Again, he looks away from the camera and appears to be contemplating what he was discovering. Whether the watering can symbolises an old ear trumpet of the nineteenth century, or whether it was supposed to symbolise Freud as a plant being watered and nurtured, mirroring his growth as an artist, is unclear. Yet, what is apparent is that Freud was highly creative in his expressions as an artist, where he chose unconventional objects or settings to symbolise his rather unconventional journey as a painter.

Located on the second floor of the National Portrait Gallery, the photograph of Lucian Freud no longer depicts an unfamiliar face. The square film negatives considerably capture Freud’s life as an artist torn between an isolated past and his new outlooks for the future. The photographs, therefore, symbolise the beginnings of his careers, which was possible even if his experiences following the rise of Nazism and his migration to London were equally as difficult to interpret or comprehend than his interaction with a watering can.