‘I first realised I wanted to study History and only History when I was 7 and visited the Tower of London on a school trip. From then on, History was the only lesson I looked forward to and became all I wanted to study all day every day.’

I’ve endured almost three years of study at Oxford and, more recently, spent hours trying to convince employers that the skills from my degree really are ‘transferable’. Reflecting now and comparing myself to others around the world in the same position, I’m forced to ask whether I really was speaking honestly at interview or if a couple of Maths or Economics courses in my third year would have served me better for the world of work ahead.

Choosing one or two subjects to study at university at 18 seems like a very normal, natural progression in the English system. Eleven subjects at GCSE, three or four at A-Level and then, finally, you pick your favourite one. Oxbridge interviews are set up not only to find the most gifted at particular subjects, but those most passionate. ‘Passion’, we’re told, is what will get us through twelve essays a term in the same subject, every term, for three years. The vast majority of university students, however, are not passionate enough to take their love of their subject further. Love for one’s subject mysteriously, and quite suddenly, peters out in the third term of one’s third year as most of us hit the job market and the idea of masters or PhD level studies terrifies us.

An education system which takes this into account, which isn’t gearing us up to fall in love or out of love with the academic profession is surely more desirable. Being forced to or even just having the option to take a wider array of courses ought to make us more attractive on the job market and prepare us for life. Taking this back further, a broader 16-18 curriculum, which doesn’t let us drop Maths, essay subjects or a language ought to leave more doors open when it comes to deciding what to pursue career-wise, giving employers tangible numerical, reasoning and language skills to refer to. However, this isn’t an argument for general studies courses or more practical education post-16. It’s a case against siloing young adults into specific departments and in favour of interdisciplinary studies.

The liberal arts program and high school curriculum in the United States speaks volumes for the advantages of an interdisciplinary education. Many universities lay out compulsory courses in essay-writing, modern foreign languages or science for freshmen and sophomores, while allowing students to pursue their interests by majoring and minoring in subjects in their final two years. It also gives university professors a lot more freedom to curate interesting, popular courses that don’t necessarily fit within a particular department’s framework. ‘Beyoncé Feminism, Rihanna Womanism: Popular Music and Black Feminist Theory’ at Harvard or ‘How to Stage a Revolution’ at MIT are two examples of ‘out-of-the-box’, interdisciplinary courses that we rarely see the likes of in the UK. In an academic climate gripped by movements to diversify the canon, encouraging universities to make their options ‘popular’, to fight it out on the ‘student market’, is surely a good thing.

The English academic’s rebuttal would be that three years of specialised learning in Biochemistry, Classics or Maths takes you to a far higher standard than one could get by taking a few ‘major’ modules a year. The liberal arts education leads to a surface-level understanding of a few subjects, without taking you to the depth of knowledge which you’d need for ‘proper research’, to really add something to the discipline with your final dissertation. There is a case for specialisation in certain subjects in which knowledge is cumulative. This is particularly evident in subjects like Law or Medicine, where the English system somewhat ‘fast-tracks’ 18-year olds and shaves a couple of years off their professional debut. However, the case for a multidisciplinary approach in the humanities and even some science subjects is strong. From personal experience, I would argue that being able to take papers in Philosophy, Economics and English would add significantly to my study of history and might mean I didn’t ignore the parts where politics becomes ‘mathsy.’ Equally, the benefits of interdisciplinary ‘modes of thinking’, applying a ‘scientific brain’ to ‘artsy questions’ have been well researched and argued.

Moreover, few would suggest that top institutions in the United States, Continental Europe, or Asia are hampered in the quality of their graduates, teaching staff or research capabilities by a secondary or tertiary education program which does not encourage specialisation. In fact, exposing students to new subjects, ones which they might not have considered at school level, can give birth to high-quality graduates and researchers whose passion for their subjects started late in their academic careers.

Multi-disciplinary study at university could also help to address this country’s youth employment or higher education crisis. Ever since increasing numbers of young people started attending university at the start of the century, cries about ‘pointless degrees’ or ‘too many people going to university’, often from the right, have dominated debates about the place of universities in society. If we do want to maintain higher education as a valuable tool for social mobility, perhaps broadening curricula, even at top universities, is the answer. Perhaps it could encourage universities like Oxford to consider our education holistically: what skills do we really want to come away with, which untapped areas do we still want to explore? This would evidently be more beneficial than a drive for first-class degrees at any cost and, in the Oxbridge context, competition between colleges and within departments. While Liberal Arts courses have popped up at a number of institutions in the UK, the norm still remains the specialised degree and the underprepared graduate.

Even the process of choosing A-Levels is a restrictive process for young people. Students are often likely to pick their options based on particular departments’ track record or the ease with which they can achieve top grades. The decision to drop a particular subject simply because of a bad teacher, department or school type is evidently restrictive and problematic. Often the case for taking a particular subject is strengthened by a particular charismatic teacher or which subjects are deemed popular. Many schools, moreover, are pressured by the harsh quantitative scrutiny of league tables to push students into taking ‘easier’ subjects or those taught by the best department. The positive feedback cycle here is damaging: worse departments with fewer students at A-Level end up receiving less funding, and so on. For certain subjects, this can also feed into a worsened state-private school divide once at university, with subjects like Classics often seen as the domain of the economic elite. With the aim of equal opportunity, therefore, a less narrow school-level education may be a solution.

The most obvious argument for specialisation at A-Level arises from the fact that everyone has different strengths. We should allow teenagers to express their individuality, choose their subjects and excel in their strengths. This is rooted in a particular view of education which sees all children as different, with different processing abilities: people think in different ways and everyone has their own strengths. Not letting people drop subjects which they’re bad at could lead to disillusionment, poor mental health, and all-round negative associations with school. Letting every teenager choose their own subjects, it is argued, allows them to engage with their interests and fulfill their potential.

A-Levels, moreover, aren’t mandatory. The standardised English education system ends at 16, with a range of options, from BTECs to the increasingly popular apprenticeship scheme, available after. Those who argue in favour of a more ‘practical’ education often focus on the fact that A-Levels are not and have been increasingly less important for career aspirations. This isn’t unique to England: Germany has ΩBerufsschule (‘vocational schools’), which allow those over 16 to study alongside a three- or four-year apprenticeship, while France has a separate stream for those who want to take the ‘vocational baccalaureate’. Mandating a core curriculum until 18 is, therefore, potentially linked to the United States’ higher high school dropout rate than the UK and more general dissatisfaction with education.

This is compounded by the fact that the A-Level system is very popular. The English Education System is, undeniably, quite highly regarded around the world. Cambridge International A-Levels are taken by the economic elites all over the world, from Hong Kong, to India, to South America. They are seen as a gateway to academic success, to prestigious higher education institutions and a demonstration of true academic mastery.

It’s important, however, to deconstruct this reverence for English schooling. Education has been an area particularly defined by the colonial experience in many countries around the world. The idea of being part of an educated super-class still runs deep and possibly shapes existing feelings of respect towards the A-Level System.

Alternatives are on offer within the UK too. Scottish schoolchildren take more subjects to Highers Level and many private schools have opted to also offer the International Baccalaureate, which forces students to pick a true range of six subjects, taking three to ‘Higher’ Level. The impact of the IB on low-income US students was found to create ‘more rigorous classrooms, students who participate in more extra-curricular subjects and who had greater higher educational aspirations.’ However, the likelihood of us as a nation or schools more generally switching to such a system appears unlikely.

Gavin Williamson, former Secretary of State for Education, recently said that the purpose of education is to ‘give students the skills for a fulfilling working life’. While the answer to this could be vocational training from a young age, I’d argue that the key to a more ‘useful’ education is to treat young people as individuals and parts of the workforce, rather than as potential future academics. A more holistic education, one which accepts a need for depth while maintaining linguistic, literary and numeracy skills developed from a young age, could reinvigorate teachers and students and improve falling university satisfaction rates.

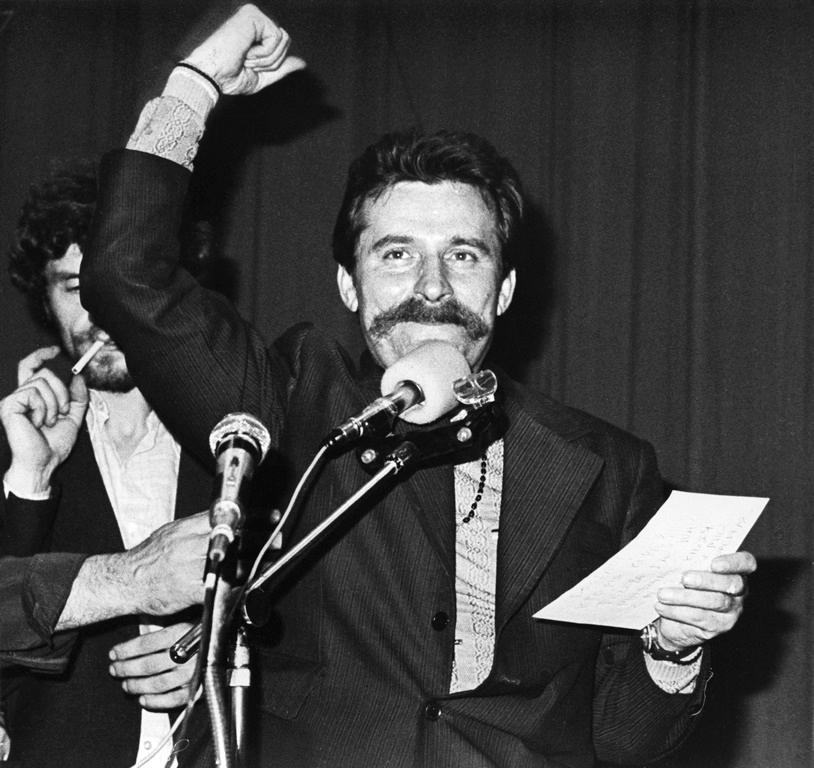

Artwork: Ben Beechener