Anyone who knows even a little about the London art market will know Frieze. Founded in 1991 as a contemporary art magazine by Oxford graduates Matthew Slotover and Amanda Sharp, the first Frieze Art Fair was held in 2012 and swiftly established itself as an internationally renowned show of contemporary works, displayed in Los Angeles, New York, and each October in Regent’s Park. Speaking to Slotover, who studied psychology at Oriel before later judging the Turner Prize, I anticipate the task of disguising my eyes wandering across his background. I imagine the large canvases which would hang behind him from his Zoom spot—though my curiosity is hampered by his placement in front of an open kitchen cupboard, mugs on display. Though, for anyone familiar with Damien Hirst’s ‘Medicine Cabinets’, perhaps I’m wrong to assume this isn’t an installation. But I can’t imagine Hirst would use a Moomins mug in one of his pieces.

As a founder of such an influential art fair as Frieze, what wonderfully artistic childhood did Slotover have? ‘I had never really been interested in contemporary art—I never looked at it when I was a kid, I never studied art. I was so bad at art that they didn’t accept me at school onto the O-Level course.’ He tells me that he did always have an interest in photography, and a photograph of his was used as the cover for a student magazine while at Oxford. But he left university having studied psychology, tossed out from the metaphorical frying pan of Oxford into the fire of the 1989 recession: ‘An old friend who was at art school in London at St Martin’s—I began to look at art exhibitions with her, and some of the first art I saw was these warehouse shows that Damian Hurst and his generation were organising.’ Slotover describes the ‘breath of fresh air’ contemporary art represented following Oxford, having never been exposed to the aesthetic stimulation of the London art world and its energetic upcoming figures.

Newfound passion discovered, Slotover began reading art magazines—though he had little choice, seeing as there were apparently only three publications worldwide: ‘I just thought it was garbage and I just could not understand the writing, I thought the design was bad, they weren’t talking about the art that I was interested in.’ Having become acquainted with the entourage of the young Hurst et al., he equally resented the treatment of those starting out—an established practice of ‘give them ten years and maybe we’ll talk about them’. Having identified a weakness in the market, and feeling confident that he could surpass his flawed contenders, so came frieze the magazine: ‘It was a total coincidence that I came out of university in ’89, just when this generation was also beginning. If I’d tried to five years earlier, or ten years later, it probably would’ve failed, but it was pure coincidence that coincided.’

But this was in the 90s—since, the rise of social media and convenience of modern technology has transformed visual culture and the logistics of the global market. What is the place of art in a time of intensified visual communication and symbolism, reinforced by a continual access to images and driven by the speed of social sharing? ‘Our attention spans have reduced in the last twenty years… mine has, certainly […] The time we spend in front of an art work has probably reduced. We’re now used to getting quicker both visually and linguistically.’ Increasingly, artists produce pieces designed to work in digital reproduction, perhaps leaning into the exposure offered by social media and the usual capitalist motivations: ‘it’s easier for art to get taken up by the credit commercially if it’s legible in reproduction.’ Though Slotover insists, somewhat troubled, that reproduction art is an entirely different experience from the physical one: ‘even with photography, the scale can be different, the tactility can be different, contexts are different […] I think anyone who sees something in reproduction and then sees it in the flesh has that kind of feeling where they realise it’s different in person.’

It seems everybody loves a little sensationalism; at least, nobody can say that their attention isn’t caught by that which is sensational, whether or not love has anything to do with it. At the centre of the international art scene, I imagine Slotover has seen some provocative stuff over the years—but he tells me that the art world is remarkably difficult to shock. ‘They enjoy shock, they like it. I have to say, that Jeff Koons series where he’s fucking Cicciolina is still one of the most shocking things I’ve seen in a gallery.’ He grins; I shift in my seat: ‘not necessarily the nudity or even the pornography—but that it’s the artist with an Italian porn star MP, who he married. I don’t think the art world has been able to deal with that, still.’ He begins suddenly coughing and gets up to get a drink, joking, ‘I’m so shocked I need to have a glass of water.’ When he sits back down, he tells me of a US performance artist named Andrea Fraser who sold an artwork which itself was a sexual encounter between her and whomever bought it, video taped in 2003. He speaks of another performance artist, the Russian Oleg Kulik, who on numerous occasions throughout the 90s assumed the persona of a dog and bit spectators’ hands in galleries. However, Slotover doesn’t mention, making for my later horror on Google Images, that works of Kulik’s include photographs of him doing unmentionable things to farm animals, with one photograph happening to resemble David Cameron’s alleged Bullingdon initiation performed on a pig’s head—except the pig head used by Kulik is still attached and seemingly alive.

But is provocation just a lazy substitute for quality? Slotover thinks that hating an artwork can often indicate that it is, in fact, rather good: ‘you can hate things because you can see exactly what the artist was trying to do and was unsuccessful at it, or you can hate things because it’s aesthetically or intellectually shocking because no one’s ever really done something like that before’. When he first saw a piece by Sarah Lucas listing various swear words, he thought it juvenile. Years later, he came to realise the gendered and political playfulness of the piece and that ‘the work she was making was deliberately ugly. But very funny and clever and actually kind of beautiful once you came around to the shocking ugliness of what it was.’ I ask cynically if an audience’s desire to be shocked indicates a lack of interest in the art itself—the same cheap thrill of reality television, a desire purely to be entertained with little intellectual challenge. Slotover puts this down to the contemporary market’s constant want of new ideas. Yet it’s an unavoidable fact that the art market is rife for spectatorship—an estimated 80% of Frieze Fair visitors come only to visit, never buy.

From the heady images of a hand-licking performance artist, I switch tack and raise the matter of auction houses, the other half of the market with whom Frieze competes for buyers’ attention. Both Sotheby’s and Christie’s having previously expanded their sales to coincide with Frieze Week; the pandemic brought reports that both houses successfully sustained sales online, a prospect considerably less hopeful for Frieze whose fairs were all cancelled. But Slotover emphasises the importance of galleries for their personal care for the artists: ‘the galleries have the long-term career of the artists at heart and the auction houses don’t.’ For Slotover, the auction houses are ‘the less interesting part of the art world’ because, as he puts it, ‘they’re just not really fulfilling a long-term social benefit.’ Yet artists can be detrimentally led by economic interest: ‘there’s a pressure on the artist that points to perhaps recreate what they’ve done before. And some dealers will say to artists—“look, can you just do me another one like this one” […] Sometimes it feels like it’s basically factory made repetition—doing multiples of things, doing them in different colours and materials, but basically, there are no new ideas coming out.’ Ultimately, monetary value and the quality of a work simply do not correspond. ‘Once you understand that no one is saying the best art is the most expensive, a lot of this prejudice about the art market being detrimental kind of goes away.’

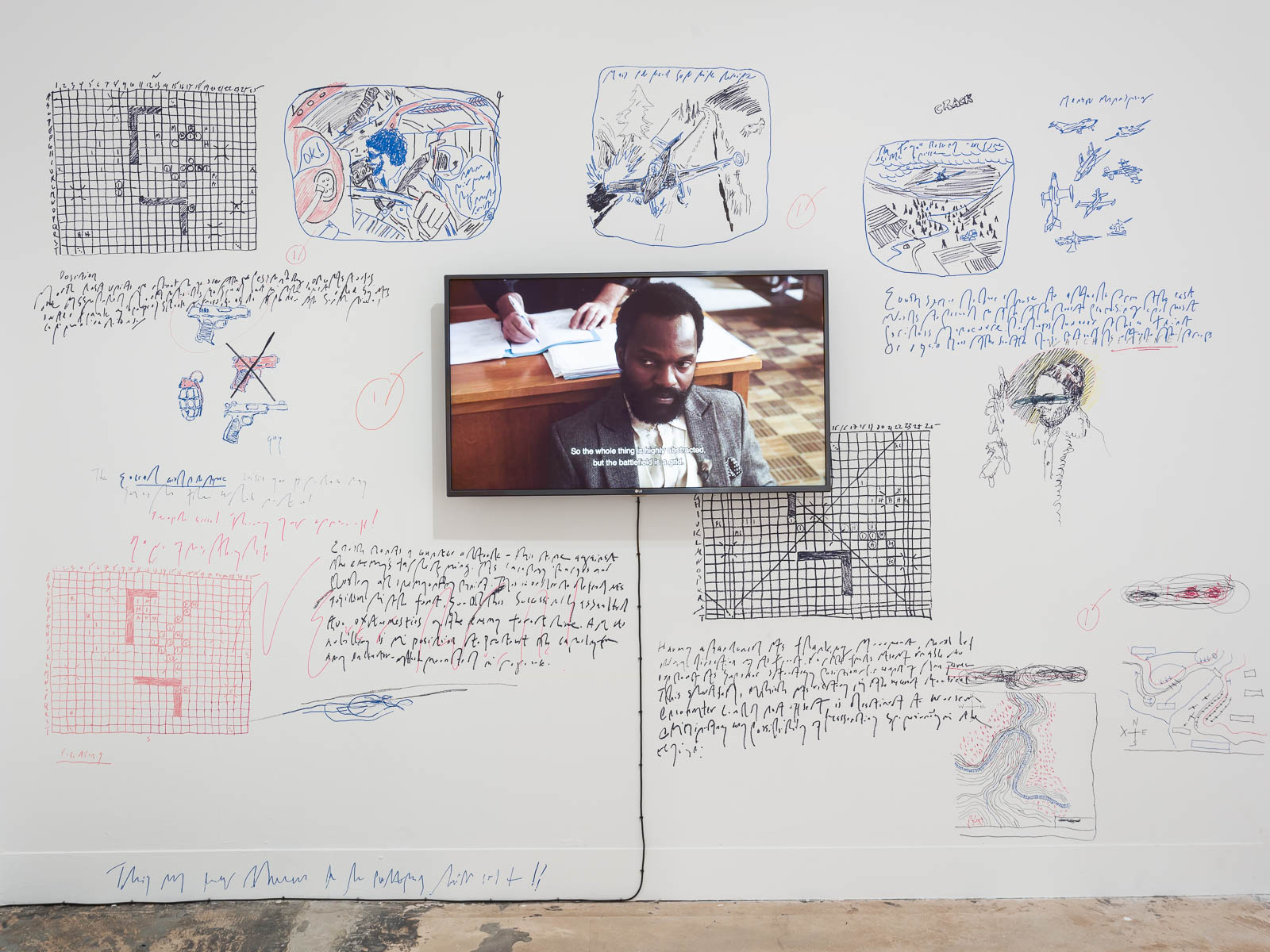

Having had a long career in the market, Slotover postulates that the globalisation of art has been influenced more by the internet in general than it has social media. With the ease of modern travel, people are far more open to art from across the world. He’s noticed rapidly expanding sales in countries in Eastern Europe and Latin America where there was little market beforehand. But he acknowledges that the undeniable effects of racial discrimination within society and the art world itself need to be confronted: he recalls attending the Tate’s Soul of a Nation which intersected art with Black power and crucially cast a much-needed spotlight on African American artists from the 60s and 70s whom had been overlooked — ‘artists that should have been recognised and clearly weren’t because of racism. They were friends of the white artists, making work in a similar vein—often much better.’ Yet while the market for non-white artists has undergone a boom in recent years, a significant monetary disparity still exists—young Western artists’ works often realise the same prices as Black masters who never had the due they deserved.

Museums, increasingly criticised for the ethics of their collections, have demonstrated a sudden keenness to diversify their collections and catch up: ‘American museums, for example, might have 1% of their collections by people of colour. But in a city like Washington, where something like 80% of the population are people of colour—how are you supposed to get those people into the museum when all they see is people who don’t look like them? They realised that a few years ago and they started aggressively buying artists of colour and that fed through to the commercial galleries.’ Even big collectors are apparently now shocked by the whiteness of their collections, and the global market is at least now enjoying the efforts to correct this. Indeed, some museums are now refusing to buy any more white artists’ works until their collections are equalised. But, as is always the case, change needs to come from the top down for it to truly take effect: ‘I think the bigger problem right now is behind the scenes, talking about people wanting to work in the market, in the art world. The people who work behind the scenes are very white. Very, very white. And very upper-middle class. That’s not changing.’ Slotover himself attended public school. ‘If you’re first-generation student finishing university and your parents want you to have a career and you say you want to be an art curator, how happy are they going to be? I’m not sure how attractive these jobs are to people who haven’t had the economic and social stability and confidence to go into it. It’s really only when the people who hold the power strings are sufficiently diverse that the art that’s being shown will really be explored, explained, shown, discussed in an equal way—which is to everyone’s benefit.’

Slotover begins to quiz me on how the pandemic has disrupted college life, and we somehow get onto the topic of Rhodes, whose statue—looming over his old college—we simultaneously lament has not yet been taken down. I’m distracted when my eyes settle back on the Moomins mug which itself looms behind the open cupboard door. With restrictions now easing, I consider the possibility of an in-person fair in October. Though if there’s one thing I’ve taken from this past year it’s that one can never predict the delays to normality which wait around the corner.