There are two questions that are raised by the annual publication of the Norrington Table. One of these is interesting and important; the other not so much. The uninteresting question concerns how we are supposed to interpret the table’s results each year. The answer is that there are many meanings that we could impute to the Table, and because of this, it’s probably best not to impute any. The more difficult question is what meaning we should ascribe to finals marks, and here it’s at best wrong and at worst stupid to say ‘they don’t matter’ or ‘so long as you do your best’ or any vaguely therapeutic-sounding pleasantry like that. Finals marks do count for quite a bit, both as a measure (albeit, a potentially bad one) of one’s intellectual ability and as a determinant of what options are available immediately after graduation.

But the importance of the second question, unfortunately, leads us to think too hard about the first one, in that it leads us to think about it at all. Since individual finals marks are highly important, there is a natural inclination to think that the aggregate finals marks of one’s college also matter. Rowers care a lot where their college places in Eights – why shouldn’t students care where their college places in finals? There is a rather prurient interest to the whole thing as well: the Norrington Table is about as close as it’s possible to get to seeing under other colleges’ skirts. It’s titillating, in the way that getting a glimpse of any closely guarded secret can be. There are, after all, people behind those marks. When we say Merton would have placed first if a few more finalists had gotten firsts, there are probably a lot of Mertonians who are thinking ‘if I had just gotten a few more marks, I would have gotten a first’.

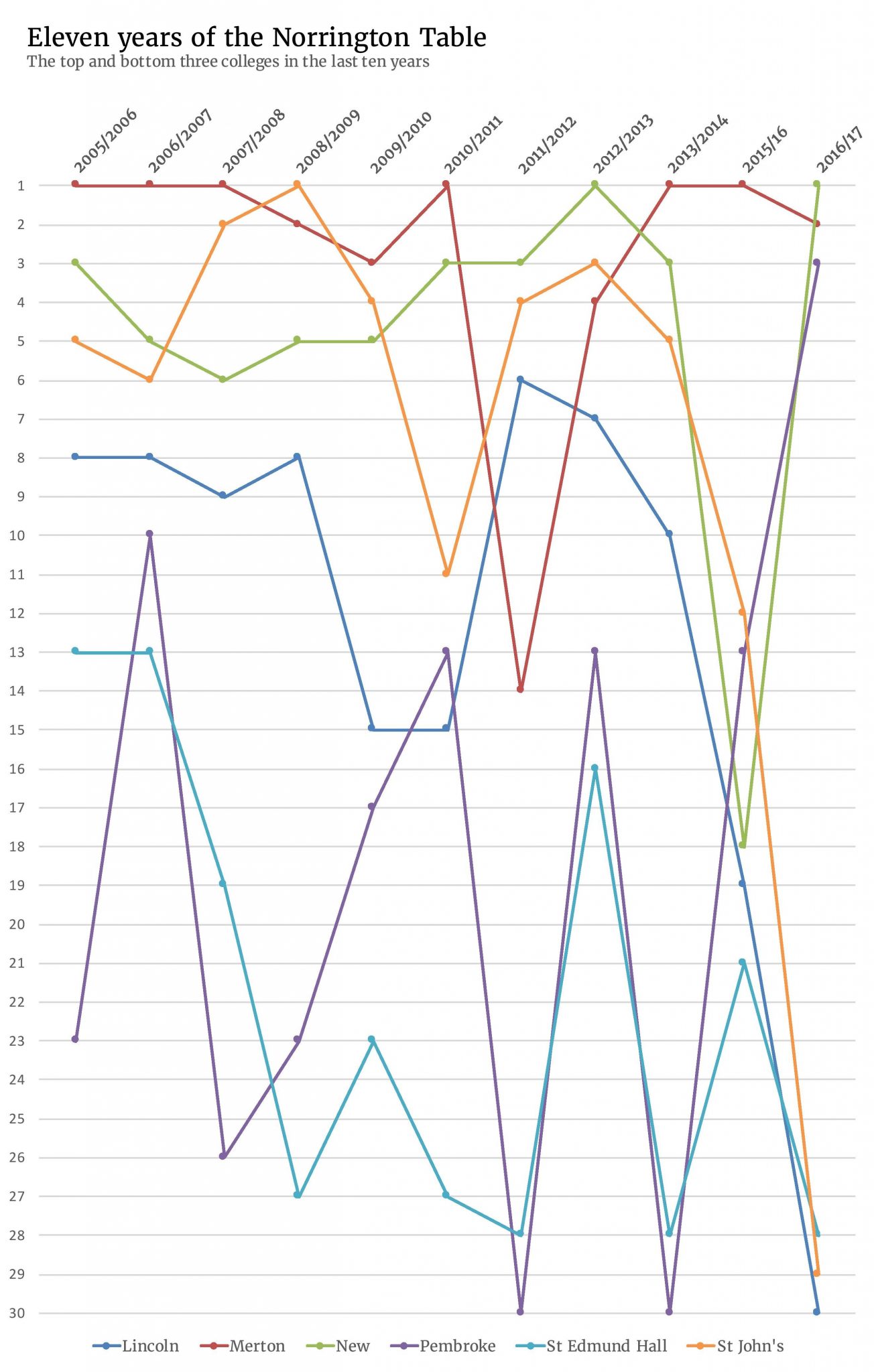

Yet there is an obvious distinction between Summer Eights and the Norrington Table. With the former, there is usually no mystery as to how exactly the race was won. But there is a very deep, and I suspect to students impenetrable, murkiness around why marks are distributed as they are. Is it significant that the top three colleges all eclipsed the previous record in finals? Should Lincoln be worried that it has plunged to the bottom of the League? How pleased should Pembroke dons be about how high they’ve climbed in the last couple years? Of course these questions have answers, but there’s no way for us to figure out what they are. There are simply too many variables at play: the proportion of students at each college studying subjects with a higher first rate; the stringency of each year’s examiners; the attitude and competitiveness of each year’s student body; the quality of instruction, both in tutorials and exam prep sessions; the astuteness of college interviewers; and so on. Maybe colleges, or the University, have access to information on each of these data points – but students certainly don’t.

In the aftermath of last year’s Norrington Table I asked what it was that the Table really measured, having taken a quick look at the relationships between League performance and different variables, like college age, wealth and popularity. It is probably worth, a year later, admitting to the crime: that kind of analysis is deliberately sensationalist; the factoids might be fun, but they’re largely empty. To the credit of the Oxford student body, I think this is widely recognised. The Norrington Table is a good excuse for a few minutes of inter-college banter, and for the most part nobody treats it as much more. But there is a real problem with according it even that level of attention; it keeps the Table firmly rooted in the University’s consciousness, and to treat it jovially is usually to fail to treat it critically. Because finals matter, how colleges perform at finals also matters. If it is actually the case that some colleges better prepare students for exams than others – and I see no reason why it wouldn’t be – then this is an inequity that needs to be addressed. But the Norrington Table, given how superficial the information it provides, fails to present a valuable insight into the problem.