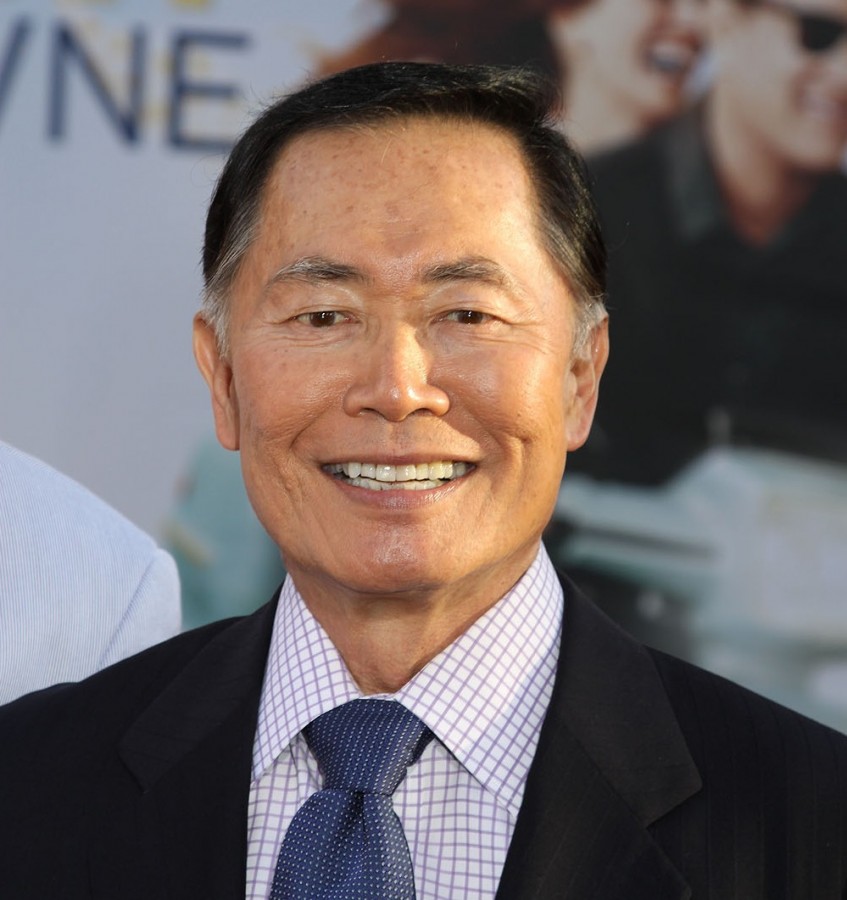

Randall Kennedy Was born in South Carolina in 1954. He attended Princeton for his bachelor’s degree, Balliol College on a Rhodes scholarship, and Yale Law School, before doing two judicial clerkships, the second for US Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall. In 1984, he accepted a teaching post at Harvard Law School, where he has stayed ever since, penning magazine articles and books on race and the law. In other words, Kennedy is an academic – and a very good one. But he is also an advocate and an intellectual: He is not only engaged in the pursuit of truth (‘Veritas’ reads Harvard’s motto), but a fighter in the world of ideas, whose scholarship is intended to be part of, and shape, the public discourse.

Kennedy is also black, and his work grapples with issues of race. He is working on two projects currently, he tells me, in his spacious office at Harvard Law School: a book of essays and a book on the consequences of the Civil Rights Movement. The projects complement each other. The first is a history of Kennedy’s work: he is revisiting, revising, and expanding upon old essays and books, addressing new developments and realisations. The second is, indirectly, a history of his life – his own and all the other lives of African-Americans born since 1954.

“There are a couple essays,” Kennedy says, that will form the core of his first book. One of them is called ‘Where is the Promised Land?’, in reference to a speech Martin Luther King Jr. gave the night before his assassination. That night, Kennedy explains, “King said to his audience ‘I might not get there with you but I’ve seen the Promised Land, and we as a people will get to the Promised Land.’ My question is, what is the racial Promised Land? What does it look like? What are its borders? What is its topography? What is it?”

“I don’t care who you are, everybody says they’re for racial justice, for racial equality. Everybody!” Kennedy continues. But what we mean by racial justice is deeply ambiguous – we have declared ourselves for racial equality and against racism, without focussing on what we mean by those terms. For example, Kennedy asks, “if you say you want a race blind society, ok, does that mean that you want the abolition of all associations that are designated by race? Does that mean that you want an end to, let’s say, the Congressional Black Caucus? Does that mean you want an end to any private association that has race in a title? Is it a bad thing for a black person to walk down the street and to interact in a special way with other black people?”

Kennedy himself admits to being unsure of the answers to these questions. One of his essays in the Atlantic speaks to racial solidarity and kinship – its thesis that politically and intellectually, the practices are indefensible. The essay stuck with me: it had taken a hard line about what I felt was a much less clear-cut issue. I ask him about it and he tells me he’s been considering “publishing that essay as is, and then responding to it.” He says something else that is remarkable as well: that he was undecided about racial solidarity even at the time he wrote the piece. “I wanted to try on that view,” he says. “Let me try this on, let me really argue for it strenuously. How will I feel about it? So I did.” But his ambivalence did not go away.

A third essay being featured in the book is on one of the long-running themes in Kennedy’s work – that in the history of American racial thought, there have been two camps: optimistic and pessimistic. The pessimists – whose ranks include Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, Malcom X, and Kennedy’s own father – say “we shall not overcome. Let’s just get that straight: America was born in racism, will remain a racist nation-state, and that should be understood.” The optimists – Frederick Douglas, Martin Luther King Jr., Barack Obama, Kennedy – disagree: we will reach that promised land.

“Now,” Kennedy says, “I’m going to revise [that essay], because, frankly, we are in the middle of a presidential election, and what has already happened is very alarming and very disturbing. And I need to talk about that. Frankly, if Donald Trump was to win the presidency – I don’t think he will – but if he was, I would really have to rethink what I wrote.” A related revision will be to his 2012 book The Persistence of the Color Line. “Did I think when I wrote that book that the backlash, that the racial backlash would be as vivid, would be as sharp, would be as deep, would be as just open and unvarnished… vocal, visceral, as it has been? Nah! I have been taken a bit by surprise.”

But the book Kennedy says he needs to revise the most is his first, Race, Crime, and the Law. Kennedy’s thesis at the time was that African-Americans have been under-protected against criminality – a conclusion drawn in 1997, before discussion of mass incarceration and the hyperpunitiveness of the American criminal justice system entered the mainstream. “I don’t talk enough about that,” Kennedy insists. “And I am going to talk about that. I made it seem as though somebody goes to prison, it is all about them. I did not talk about the way in which everybody is part of a web. If some person goes to prison, it’s not just about them. What about their kids? What about their parents? What about their cousins? What about their neighbours?”

Another Of The compendium’s essays will be about Derrick Bell, briefly a colleague of Kennedy’s at Harvard and an “ideological adversary” for a long time afterwards (Bell died in 2011). Following the publication of Race, Crime, and the Law, Bell wrote an essay in New Politics declaring Kennedy “the impartial, black intellectual, commenting on our still benighted condition and as ready to criticize as commend.” His criticism amounts to this: Kennedy, for reasons of naivety or personal indulgence, has betrayed the civil rights movement; his positions only harm the cause, providing “a comfort to conservatives and advocates of the status quo.”

Consider the severity of this attack. Kennedy is enormously thoughtful; he is highly animated and cares tremendously about his work; and he considers himself a fervent supporter of American liberalism. Bell’s article, then, goes after the core of Kennedy’s intellectual identity – and Kennedy was harsh about Bell as well. But nevertheless, Kennedy says, “I am writing about him because I don’t think he’s ever gotten his due. I don’t think I gave him his due when he was alive. And I think he was an important person, who warrants a good, careful, rigorous examination. Any intellectual, that’s what they want.”

One of the subjects over which Kennedy and Bell disagreed most was the responsibility of the black intellectual. “I do various things,” Kennedy says. “There have been times when I have been a polemicist, really pushed hard.” He cites his work concerning interracial adoption. “I was involved in litigation about it. I was involved in lobbying. I lobbied Congress to pass a law, and was very successful in doing so. In those years, I was very much the polemicist: here is the subject, here is the way you should think about it. I was take no prisoners, very single-minded. I portrayed the other side, but I did not give much scope to it. I portrayed the other side in order to knock it down. But that is unusual for me. That has not been my typical way of being. My typical way of being is to be a little bit more cool, more distant, more appreciative of the other side, more interested in just setting forth for the reader the ironies, the paradoxes, the complications of things, and not being as much of an advocate for a particular view.”

Kennedy points out that Bell has not been the only one to take him to task for this approach. “I’ve had students who have gotten really impatient with me, who say, we are engaged in a struggle, and you act as if you’re just an aesthete. You’re talking about this as if we were talking about a poem.” On one level, he argues that this line of criticism is misguided: that the more effective strategy of persuasion is to be able to convince “a reader that if they read something by me, they are actually going to get a very rounded view of the subject.” He claims that his most recent book, For Discrimination: Race, Affirmative Action, and the Law, was able to bring people around in support of affirmative action by not pulling any punches – just proving that its arguments were stronger.

More fundamentally, however – and I think, more compellingly – Kennedy questions the logic of implying that the critic’s contributions are not worthwhile. His work can be meaningful, he suggests, regardless of whether it is successful advocacy. “If I am writing about a phenomenon like the 1964 Civil Rights Act, I think if I allow somebody to really learn about this phenomenon, I think I’ve contributed to the world. The more detailed, the more subtle, the more I allow people to understand why there were people who were against the 1964 Civil Rights Act, I think that is a contribution in and of itself, and I feel completely comfortable with that. Intellectual life is broad. It calls for different performances at different times.”

Another fundamental point of tension between Kennedy and Bell was over the optimism that pervades Kennedy’s work and thought. We will overcome. A compelling argument will succeed in changing hearts and minds. The same spirit of optimism also motivates his book exploring the impacts of the civil rights movement. The same year Kennedy was born, 1954, the Supreme Court also ruled school segregation unconstitutional in Brown v. Board of Education. “Now, has that been evaded?” Kennedy asks. “Are there public officials that engage in invidious racial discrimination through subterfuge? Yeah, sure, absolutely. But it is unlawful. They are not doing that legitimately. That was changed – and that is very important. It’s very important. So nowadays, since 1954, public officials – do they do that sort of thing? Yeah, they do that sort of thing. But they have got to lie about it!”

“I feel absolutely inspired writing this book,” Kennedy adds. “In a way it’s the story of my life. Did the Civil Rights Movement change my life? Absolutely! Are you nuts? Yes! Where are you talking with me? Harvard Law School for God’s sakes. When you come to Harvard Law School in the entering class, in 1954 there might have been, maybe there was one black student, maybe. Maybe there were two. Not more! Entering class at Harvard Law School now, you got to make sure that you have got a class that can contain the African American contingent of students.”

The book is also an ode to American racial liberalism, to the thinking “that repudiates the idea that white people should be on top, that white people have a right to run things, that white people should, of course, have first dibs on the best of American life.” Kennedy reiterates that there is still far to go (“the United States is still a pigmentocracy, even with Barack Obama in the White House”), but he lauds the achievements of the Second Reconstruction – the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the 1965 Voting Rights Act, Brown v. Board of Education – as “the great landmarks of liberalism” and progressivism. “I’m no Pollyanna,” he says, but “people of my political ilk should be proud of that.”

In November Of last year, portraits of Harvard Law School’s African-American professors were defaced with black tape. The student body was outraged and upset: this was, many believed, an unequivocal case of racism – and emblematic of a deeper, systemic racism with the institution. “As a black student, it was extremely offensive,” the president of the student body told the New York Times. “And I know the investigation’s ongoing; we’ll see what happened, but to me it seemed like a pretty clear act of intolerance, racism.”

To Kennedy, it wasn’t so clear. In a Times op-ed published a week later he urged reflection and suggested other plausible explanations for the incident besides racism. Even “assuming that it was a racist gesture,” he wrote, “there is a need to calibrate carefully its significance. On a campus containing thousands of students, faculty members and staff, one should not be surprised or unglued by an instance or even a number of instances of racism.” He warns as well against a “tendency to indulge in self-diminishment by displaying an excessive vulnerability to perceived and actual slights and insults.”

New York Times commentators were appreciative; many students were not. On December 5, Two activists respond to Kennedy’s op-ed in the Harvard Law Record. For paragraph after paragraph, they tell him he is missing the point, insensitive to the systemic racism at play, diminishing the student body. “He is redefining racism and trivializing the experience, insights, and courage of the students who perceive something that he doesn’t,” they write. “He may unwittingly be a source of [black students’] disempowerment.”

A steeliness in Kennedy’s voice emerges when I ask him about the incident. “I think there were some people who viewed me an ideological enemy of the antiracists within Harvard Law School,” he says. “And it seems to me that they were profoundly mistaken.” The steeliness fades into frustration. “I talk with students about this all the time. I’ve said, first of all, since when is being a critic necessarily – you view me as being an enemy because I was being critical of you? Oftentimes, criticism is friendly. I was trying to be your friend.”

“You want people to save you from yourself,” Kennedy says. “Do I think that every time I write something, I’ve got it perfect? No! I don’t! I am all the time writing, sending out drafts to people, and either implicitly or explicitly, I am asking people, save me from myself. So, as far as I was concerned, I was an ally saying, hey listen, I think a lot of what you’re doing is good, but you’re strong. Glory in that. Why talk yourself into being weak? I think some of you guys are talking yourselves into being weak. ‘I’m so traumatized by this, I can’t study anymore.’ Nah, nah, nah, I see you guys, I talk with you, you’re in my classes. I’ve seen you. You’re strong.”

Kennedy does acknowledge a narrowness to his definition of racism. “I tend to be a little bit more demanding in evidence. So for instance, when this incident happened, I went around to people, and I said, Gosh, you are really so angry, you are really so alienated. I’m here, I’ve been a long time here, I must see things differently. Give me some examples of why you feel disrespected, so deeply alienated from Harvard Law School. Because I don’t understand. And then we would talk, and people would give me an example, and I would say, to tell you the truth, just given the example that you just gave, I don’t see it the way you see it. You see it as racism. I am not persuaded of that. There are a bunch of other alternative explanations. You just gave me an example – why do you think it is racism as opposed to somebody being a jackass? There are jackasses around. Maybe it is racism! I’m not saying it’s not. On the other hand, maybe it’s not.”

“Racism has a particular status in our society,” he adds. “If you are going to say that the institution is racist, yeah, well, people who are predisposed to go along with you might go along with you, just because you said it. But there are going to be a lot of people who, nah, they’re not going to go along with you just because you just said it. In fact, they may be very skeptical of you. How do you get through their skepticism, how do you draw them onto your side? I am training advocates for God’s sakes.

“And I should say one more thing: one thing that I think that came up after that piece, because there were some people here, some activists, who were very angry with me. One thing that I ultimately said to them is you need to be very careful in dealing with people, including me. Because you can make enemies out of people. I wrote the piece I think very much as a critical ally as yours. But some of you are acting in a way that if you are not careful, you are going to make an enemy out of me, and I would advise you not to do that, because frankly you’ve got enough enemies. Why make an enemy out of an ally? That doesn’t make any practical political sense. But you seem to be doing that from time to time. That, it seems to me, is something that you would want very much to avoid doing.”

Similar Struggles Over the boundaries of racism and discrimination have been playing out across higher education campuses. Protests have erupted over cultural appropriation, controversial speakers, ‘triggering’ content in course material, and – in the variation certainly most familiar to the Oxford student – institutional commemorations of bigoted historical figures. Does Oriel’s statue of Cecil Rhodes signal that Oxford is an exclusionary space? How about a residential college named after an unapologetic defender of slavery? Or a law school crest that pays homage to a slave-owning family?

These questions are the foundation of what Kennedy calls the “dememorialisation struggles”: on the one hand are student-led calls to eliminate symbols celebrating racists and bigots; on the other, there are cries to preserve history and the sanctity of free speech. We had Rhodes Must Fall here at Oxford; Princeton saw protests over the Woodrow Wilson School; Yale over Calhoun College; Harvard over the Royall Crest. There have been similar denunciations of vestiges of the Confederacy, like statues of Confederate soldiers and representations of the Confederate flag.

“For all of these,” Kennedy says, “my basic thing is, as a presumption, addition rather than subtraction. I don’t want people to lose sight, too much, of what’s in the past. Yeah, there was a guy named Robert E Lee, and Robert E Lee was a quite substantial person, admirable in certain respects, but this person who was admirable in certain respects fought for the Confederacy, which was willing to go to war to maintain a system that allowed for and that actually reinforced a regime of making people property. I want people to remember that boy, wasn’t that screwed up? And didn’t even people who were admirable in certain ways fall into that? That’s a hell of a cautionary tale. I want the cautionary tales to stick around.”

“Now, when somebody talks about Thomas Jefferson,” he continues. “I want the Jefferson story to be fully out there. Here’s this guy who wrote wonderful things about liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, and all men are created equal, and he was a damned hypocrite. I want that out there too, I want the whole thing out there, but we are going to keep the Jefferson Memorial. Okay, I can live with that. And I would say the same thing, by the way, about Rhodes.”

At the beginning of my conversation with him, Kennedy told me the advice he always gives to American students heading to Oxford – a lesson based on the deep regret he says he feels about how he treated his time at Balliol. And maybe it applies here too, to those of us who risk letting Oxford’s flaws blind us to the privilege of being able to study within its walls. His suggestion was this: Be in awe. Be impressed. And take advantage of the opportunity for deep reading and study at this unique academic institution.

Profile: Randall Kennedy

Randall Kennedy Was born in South Carolina in 1954. He attended Princeton for his bachelor’s degree, Balliol College on a Rhodes scholarship, and Yale Law School, before doing two judicial clerkships, the second for US Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall. In 1984, he accepted a teaching post at Harvard Law School, where he has stayed ever since, penning magazine articles and books on race and the law. In other words, Kennedy is an academic – and a very good one. But he is also an advocate and an intellectual: He is not only engaged in the pursuit of truth (‘Veritas’ reads Harvard’s motto), but a fighter in the world of ideas, whose scholarship is intended to be part of, and shape, the public discourse.

Kennedy is also black, and his work grapples with issues of race. He is working on two projects currently, he tells me, in his spacious office at Harvard Law School: a book of essays and a book on the consequences of the Civil Rights Movement. The projects complement each other. The first is a history of Kennedy’s work: he is revisiting, revising, and expanding upon old essays and books, addressing new developments and realisations. The second is, indirectly, a history of his life – his own and all the other lives of African-Americans born since 1954.

“There are a couple essays,” Kennedy says, that will form the core of his first book. One of them is called ‘Where is the Promised Land?’, in reference to a speech Martin Luther King Jr. gave the night before his assassination. That night, Kennedy explains, “King said to his audience ‘I might not get there with you but I’ve seen the Promised Land, and we as a people will get to the Promised Land.’ My question is, what is the racial Promised Land? What does it look like? What are its borders? What is its topography? What is it?”

“I don’t care who you are, everybody says they’re for racial justice, for racial equality. Everybody!” Kennedy continues. But what we mean by racial justice is deeply ambiguous – we have declared ourselves for racial equality and against racism, without focussing on what we mean by those terms. For example, Kennedy asks, “if you say you want a race blind society, ok, does that mean that you want the abolition of all associations that are designated by race? Does that mean that you want an end to, let’s say, the Congressional Black Caucus? Does that mean you want an end to any private association that has race in a title? Is it a bad thing for a black person to walk down the street and to interact in a special way with other black people?”

Kennedy himself admits to being unsure of the answers to these questions. One of his essays in the Atlantic speaks to racial solidarity and kinship – its thesis that politically and intellectually, the practices are indefensible. The essay stuck with me: it had taken a hard line about what I felt was a much less clear-cut issue. I ask him about it and he tells me he’s been considering “publishing that essay as is, and then responding to it.” He says something else that is remarkable as well: that he was undecided about racial solidarity even at the time he wrote the piece. “I wanted to try on that view,” he says. “Let me try this on, let me really argue for it strenuously. How will I feel about it? So I did.” But his ambivalence did not go away.

A third essay being featured in the book is on one of the long-running themes in Kennedy’s work – that in the history of American racial thought, there have been two camps: optimistic and pessimistic. The pessimists – whose ranks include Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, Malcom X, and Kennedy’s own father – say “we shall not overcome. Let’s just get that straight: America was born in racism, will remain a racist nation-state, and that should be understood.” The optimists – Frederick Douglas, Martin Luther King Jr., Barack Obama, Kennedy – disagree: we will reach that promised land.

“Now,” Kennedy says, “I’m going to revise [that essay], because, frankly, we are in the middle of a presidential election, and what has already happened is very alarming and very disturbing. And I need to talk about that. Frankly, if Donald Trump was to win the presidency – I don’t think he will – but if he was, I would really have to rethink what I wrote.” A related revision will be to his 2012 book The Persistence of the Color Line. “Did I think when I wrote that book that the backlash, that the racial backlash would be as vivid, would be as sharp, would be as deep, would be as just open and unvarnished… vocal, visceral, as it has been? Nah! I have been taken a bit by surprise.”

But the book Kennedy says he needs to revise the most is his first, Race, Crime, and the Law. Kennedy’s thesis at the time was that African-Americans have been under-protected against criminality – a conclusion drawn in 1997, before discussion of mass incarceration and the hyperpunitiveness of the American criminal justice system entered the mainstream. “I don’t talk enough about that,” Kennedy insists. “And I am going to talk about that. I made it seem as though somebody goes to prison, it is all about them. I did not talk about the way in which everybody is part of a web. If some person goes to prison, it’s not just about them. What about their kids? What about their parents? What about their cousins? What about their neighbours?”

Another Of The compendium’s essays will be about Derrick Bell, briefly a colleague of Kennedy’s at Harvard and an “ideological adversary” for a long time afterwards (Bell died in 2011). Following the publication of Race, Crime, and the Law, Bell wrote an essay in New Politics declaring Kennedy “the impartial, black intellectual, commenting on our still benighted condition and as ready to criticize as commend.” His criticism amounts to this: Kennedy, for reasons of naivety or personal indulgence, has betrayed the civil rights movement; his positions only harm the cause, providing “a comfort to conservatives and advocates of the status quo.”

Consider the severity of this attack. Kennedy is enormously thoughtful; he is highly animated and cares tremendously about his work; and he considers himself a fervent supporter of American liberalism. Bell’s article, then, goes after the core of Kennedy’s intellectual identity – and Kennedy was harsh about Bell as well. But nevertheless, Kennedy says, “I am writing about him because I don’t think he’s ever gotten his due. I don’t think I gave him his due when he was alive. And I think he was an important person, who warrants a good, careful, rigorous examination. Any intellectual, that’s what they want.”

One of the subjects over which Kennedy and Bell disagreed most was the responsibility of the black intellectual. “I do various things,” Kennedy says. “There have been times when I have been a polemicist, really pushed hard.” He cites his work concerning interracial adoption. “I was involved in litigation about it. I was involved in lobbying. I lobbied Congress to pass a law, and was very successful in doing so. In those years, I was very much the polemicist: here is the subject, here is the way you should think about it. I was take no prisoners, very single-minded. I portrayed the other side, but I did not give much scope to it. I portrayed the other side in order to knock it down. But that is unusual for me. That has not been my typical way of being. My typical way of being is to be a little bit more cool, more distant, more appreciative of the other side, more interested in just setting forth for the reader the ironies, the paradoxes, the complications of things, and not being as much of an advocate for a particular view.”

Kennedy points out that Bell has not been the only one to take him to task for this approach. “I’ve had students who have gotten really impatient with me, who say, we are engaged in a struggle, and you act as if you’re just an aesthete. You’re talking about this as if we were talking about a poem.” On one level, he argues that this line of criticism is misguided: that the more effective strategy of persuasion is to be able to convince “a reader that if they read something by me, they are actually going to get a very rounded view of the subject.” He claims that his most recent book, For Discrimination: Race, Affirmative Action, and the Law, was able to bring people around in support of affirmative action by not pulling any punches – just proving that its arguments were stronger.

More fundamentally, however – and I think, more compellingly – Kennedy questions the logic of implying that the critic’s contributions are not worthwhile. His work can be meaningful, he suggests, regardless of whether it is successful advocacy. “If I am writing about a phenomenon like the 1964 Civil Rights Act, I think if I allow somebody to really learn about this phenomenon, I think I’ve contributed to the world. The more detailed, the more subtle, the more I allow people to understand why there were people who were against the 1964 Civil Rights Act, I think that is a contribution in and of itself, and I feel completely comfortable with that. Intellectual life is broad. It calls for different performances at different times.”

Another fundamental point of tension between Kennedy and Bell was over the optimism that pervades Kennedy’s work and thought. We will overcome. A compelling argument will succeed in changing hearts and minds. The same spirit of optimism also motivates his book exploring the impacts of the civil rights movement. The same year Kennedy was born, 1954, the Supreme Court also ruled school segregation unconstitutional in Brown v. Board of Education. “Now, has that been evaded?” Kennedy asks. “Are there public officials that engage in invidious racial discrimination through subterfuge? Yeah, sure, absolutely. But it is unlawful. They are not doing that legitimately. That was changed – and that is very important. It’s very important. So nowadays, since 1954, public officials – do they do that sort of thing? Yeah, they do that sort of thing. But they have got to lie about it!”

“I feel absolutely inspired writing this book,” Kennedy adds. “In a way it’s the story of my life. Did the Civil Rights Movement change my life? Absolutely! Are you nuts? Yes! Where are you talking with me? Harvard Law School for God’s sakes. When you come to Harvard Law School in the entering class, in 1954 there might have been, maybe there was one black student, maybe. Maybe there were two. Not more! Entering class at Harvard Law School now, you got to make sure that you have got a class that can contain the African American contingent of students.”

The book is also an ode to American racial liberalism, to the thinking “that repudiates the idea that white people should be on top, that white people have a right to run things, that white people should, of course, have first dibs on the best of American life.” Kennedy reiterates that there is still far to go (“the United States is still a pigmentocracy, even with Barack Obama in the White House”), but he lauds the achievements of the Second Reconstruction – the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the 1965 Voting Rights Act, Brown v. Board of Education – as “the great landmarks of liberalism” and progressivism. “I’m no Pollyanna,” he says, but “people of my political ilk should be proud of that.”

In November Of last year, portraits of Harvard Law School’s African-American professors were defaced with black tape. The student body was outraged and upset: this was, many believed, an unequivocal case of racism – and emblematic of a deeper, systemic racism with the institution. “As a black student, it was extremely offensive,” the president of the student body told the New York Times. “And I know the investigation’s ongoing; we’ll see what happened, but to me it seemed like a pretty clear act of intolerance, racism.”

To Kennedy, it wasn’t so clear. In a Times op-ed published a week later he urged reflection and suggested other plausible explanations for the incident besides racism. Even “assuming that it was a racist gesture,” he wrote, “there is a need to calibrate carefully its significance. On a campus containing thousands of students, faculty members and staff, one should not be surprised or unglued by an instance or even a number of instances of racism.” He warns as well against a “tendency to indulge in self-diminishment by displaying an excessive vulnerability to perceived and actual slights and insults.”

New York Times commentators were appreciative; many students were not. On December 5, Two activists respond to Kennedy’s op-ed in the Harvard Law Record. For paragraph after paragraph, they tell him he is missing the point, insensitive to the systemic racism at play, diminishing the student body. “He is redefining racism and trivializing the experience, insights, and courage of the students who perceive something that he doesn’t,” they write. “He may unwittingly be a source of [black students’] disempowerment.”

A steeliness in Kennedy’s voice emerges when I ask him about the incident. “I think there were some people who viewed me an ideological enemy of the antiracists within Harvard Law School,” he says. “And it seems to me that they were profoundly mistaken.” The steeliness fades into frustration. “I talk with students about this all the time. I’ve said, first of all, since when is being a critic necessarily – you view me as being an enemy because I was being critical of you? Oftentimes, criticism is friendly. I was trying to be your friend.”

“You want people to save you from yourself,” Kennedy says. “Do I think that every time I write something, I’ve got it perfect? No! I don’t! I am all the time writing, sending out drafts to people, and either implicitly or explicitly, I am asking people, save me from myself. So, as far as I was concerned, I was an ally saying, hey listen, I think a lot of what you’re doing is good, but you’re strong. Glory in that. Why talk yourself into being weak? I think some of you guys are talking yourselves into being weak. ‘I’m so traumatized by this, I can’t study anymore.’ Nah, nah, nah, I see you guys, I talk with you, you’re in my classes. I’ve seen you. You’re strong.”

Kennedy does acknowledge a narrowness to his definition of racism. “I tend to be a little bit more demanding in evidence. So for instance, when this incident happened, I went around to people, and I said, Gosh, you are really so angry, you are really so alienated. I’m here, I’ve been a long time here, I must see things differently. Give me some examples of why you feel disrespected, so deeply alienated from Harvard Law School. Because I don’t understand. And then we would talk, and people would give me an example, and I would say, to tell you the truth, just given the example that you just gave, I don’t see it the way you see it. You see it as racism. I am not persuaded of that. There are a bunch of other alternative explanations. You just gave me an example – why do you think it is racism as opposed to somebody being a jackass? There are jackasses around. Maybe it is racism! I’m not saying it’s not. On the other hand, maybe it’s not.”

“Racism has a particular status in our society,” he adds. “If you are going to say that the institution is racist, yeah, well, people who are predisposed to go along with you might go along with you, just because you said it. But there are going to be a lot of people who, nah, they’re not going to go along with you just because you just said it. In fact, they may be very skeptical of you. How do you get through their skepticism, how do you draw them onto your side? I am training advocates for God’s sakes.

“And I should say one more thing: one thing that I think that came up after that piece, because there were some people here, some activists, who were very angry with me. One thing that I ultimately said to them is you need to be very careful in dealing with people, including me. Because you can make enemies out of people. I wrote the piece I think very much as a critical ally as yours. But some of you are acting in a way that if you are not careful, you are going to make an enemy out of me, and I would advise you not to do that, because frankly you’ve got enough enemies. Why make an enemy out of an ally? That doesn’t make any practical political sense. But you seem to be doing that from time to time. That, it seems to me, is something that you would want very much to avoid doing.”

Similar Struggles Over the boundaries of racism and discrimination have been playing out across higher education campuses. Protests have erupted over cultural appropriation, controversial speakers, ‘triggering’ content in course material, and – in the variation certainly most familiar to the Oxford student – institutional commemorations of bigoted historical figures. Does Oriel’s statue of Cecil Rhodes signal that Oxford is an exclusionary space? How about a residential college named after an unapologetic defender of slavery? Or a law school crest that pays homage to a slave-owning family?

These questions are the foundation of what Kennedy calls the “dememorialisation struggles”: on the one hand are student-led calls to eliminate symbols celebrating racists and bigots; on the other, there are cries to preserve history and the sanctity of free speech. We had Rhodes Must Fall here at Oxford; Princeton saw protests over the Woodrow Wilson School; Yale over Calhoun College; Harvard over the Royall Crest. There have been similar denunciations of vestiges of the Confederacy, like statues of Confederate soldiers and representations of the Confederate flag.

“For all of these,” Kennedy says, “my basic thing is, as a presumption, addition rather than subtraction. I don’t want people to lose sight, too much, of what’s in the past. Yeah, there was a guy named Robert E Lee, and Robert E Lee was a quite substantial person, admirable in certain respects, but this person who was admirable in certain respects fought for the Confederacy, which was willing to go to war to maintain a system that allowed for and that actually reinforced a regime of making people property. I want people to remember that boy, wasn’t that screwed up? And didn’t even people who were admirable in certain ways fall into that? That’s a hell of a cautionary tale. I want the cautionary tales to stick around.”

“Now, when somebody talks about Thomas Jefferson,” he continues. “I want the Jefferson story to be fully out there. Here’s this guy who wrote wonderful things about liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, and all men are created equal, and he was a damned hypocrite. I want that out there too, I want the whole thing out there, but we are going to keep the Jefferson Memorial. Okay, I can live with that. And I would say the same thing, by the way, about Rhodes.”

At the beginning of my conversation with him, Kennedy told me the advice he always gives to American students heading to Oxford – a lesson based on the deep regret he says he feels about how he treated his time at Balliol. And maybe it applies here too, to those of us who risk letting Oxford’s flaws blind us to the privilege of being able to study within its walls. His suggestion was this: Be in awe. Be impressed. And take advantage of the opportunity for deep reading and study at this unique academic institution.